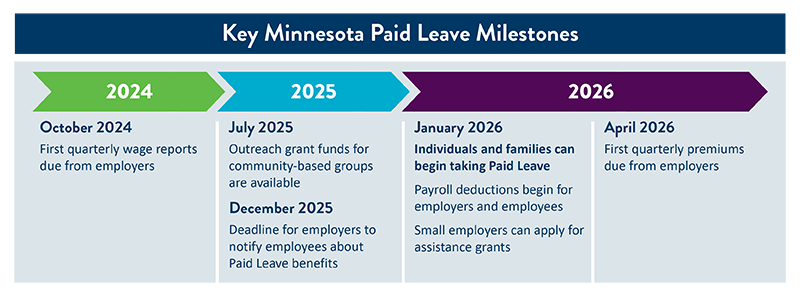

Paid Leave benefits will start for Minnesotans on January 1, 2026.

Paid Leave is a new program launching for Minnesotans in 2026. It provides paid time off when a serious health condition prevents you from working, when you need time to care for a family member or a new child, for certain military-related events or for certain personal safety issues.

There are two main types of leave:

- Family Leave to care for a family member with a serious health condition, or if you're bonding with a new baby or child in your family.

- Medical Leave when your own serious health condition prevents you from working.

Additionally, you will be able to take leave to support a family member called to active duty, or if you or a family member are facing a significant personal safety issue.