The presence of such industry powerhouses as Polaris, Arctic Cat and New Flyer make Northwest Minnesota a hub of transportation equipment manufacturing.

The presence of such industry powerhouses as Polaris, Arctic Cat and New Flyer make Northwest Minnesota a hub of transportation equipment manufacturing.

From wheat and potatoes to soybeans and sugar beets, the region is a major producer and processor of food staples and specialty agricultural products.

Want the freshest data delivered by email? Subscribe to our regional newsletters.

6/29/2016 12:04:56 PM

Chet Bodin

Understanding costs and benefits of post-secondary education is important for anyone looking to improve their job prospects, whether it be high school seniors or mid-level professionals who want to make a career jump. Last month’s blog post on the Rising Costs of College looked at the total costs of several types of degrees when personal expenses and education grants are factored into normal cost considerations like tuition, room and board and books.

But how do incurred education costs look after graduation? This month we track employment outcome data from state college and universities in Northwest Minnesota to find out where post-secondary graduates stand financially after they enter the workforce.

As noted in last month’s post, the major difference in education costs comes from the accumulated amount of multi-year programs – and the additional interest on what is borrowed to complete a degree. Borrowers have several options to cover these costs, including private loans from banking and credit union institutions. However, most first-year, full-time students are eligible for federally-subsidized loans with 4.66 percent interest.

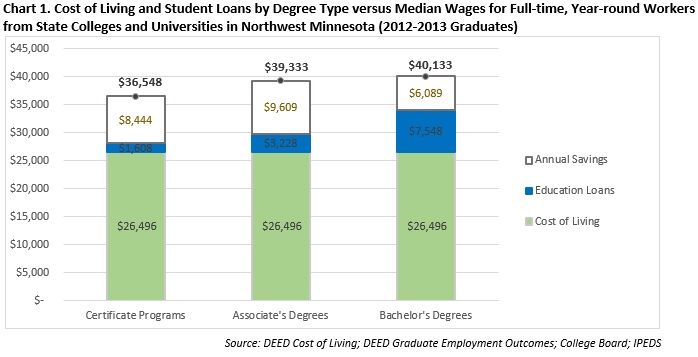

Based on that rate, certificate completers paying off $12,905 in student loans from fully financing one year of college would need to pay $1,608 per year over a 10-year period. Associate degree holders who compiled $25,810 in loans in two years would pay $3,228 per year for 10 years; and students who borrowed $60,248 over four years to earn a bachelor’s degree would have annual payments of $7,548 over 10 years.

After graduating and joining the labor force, in addition to student loans, these workers often start accumulating regular expenses like housing, food, insurance, transportation, and more. According to DEED’s Cost of Living tool, the basic needs budget for a single person with no children in Northwest Minnesota is $26,496, regardless of educational attainment.

Looking at wages of graduates from the five public colleges (Alexandria Technical & Community College, Central Lakes College, Minnesota State Community and Technical College, Northwest Technical College, and Northland Community & Technical College) and two universities (Bemidji State University and Minnesota State University, Moorhead) in Northwest Minnesota, DEED’s Graduate Employment Outcomes tool shows that the median earnings for full-time, year-round workers with one- and two-year degrees made just slightly less in their second year after graduating; but because of their lower loan payments these graduates would have more net income than four-year degree holders who found full-time, year-round work after joining the workforce (Chart 1).

Given these incomes, a certificate holder working full-time, year-round would have nearly $2,400 more in financial freedom than a four-year degree holder two years after graduating, and a person with an associate degree would have $3,500 more in-pocket. Though the data show that not all graduates are able to find full-time, year-round employment immediately after graduating, that is often the goal for these students. For 2013 graduates, 43 percent of people earning certificates found full-time employment, just ahead of those with bachelor’s degrees (39 percent) and associate degrees (37 percent).

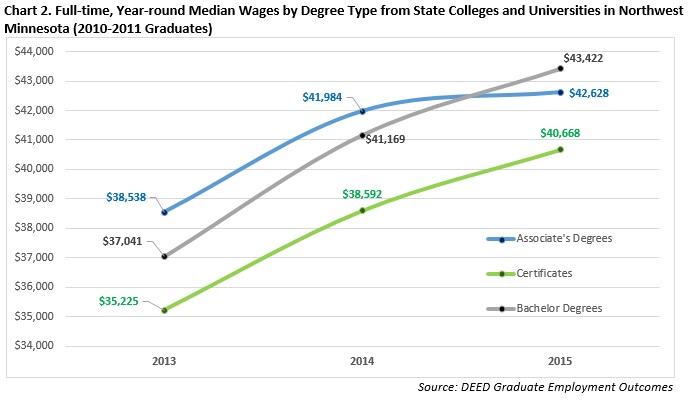

However, full-time wages tend to fluctuate by degree type over time once graduates become more established in the workforce. Looking at data for graduates from 2010-2011, wages for those with bachelor’s degrees exceeded those with associate’s degrees by about $800 annually in their fourth year (Chart 2). While it’s important to track changes over time, the median wages of bachelor’s and associate degree graduates from 2011 were nearly equidistant in 2015 to graduates who attained those degrees in 2013. In other words, 2011 graduates with associate degrees who found full-time employment would have had an opportunity to save well over $10,000 more than bachelor’s degree holders after four years in the workforce.

The data show that certificates and associate degrees lead to slightly lower wage levels but much lower educational costs with more manageable payments after completion. If a person’s occupational goals require a bachelor’s degree, that requires more short-term and long-term comparisons. Understanding the resulting debt-to-income ratios could help anyone just starting out in their career or those readjusting mid-career. If one- and two-year degree holders choose to pay their loans off faster with the extra income, they could also save significant amounts of loan interest; graduates with bachelor’s degrees may be banking on higher returns over time.

Of course, others with families to support may need the extra dollars to cover cost-of-living expenses for childcare, food, or housing. Next month we’ll look at how educational attainment impacts the cost of living for different family types in Northwest Minnesota.

Contact Chet Bodin.