by Cameron Macht and Anthony Schaffhauser, Director of Healthcare Workforce Development at HealthForce Minnesota

December 2021

Our state, like much of the nation, is experiencing an unprecedented health care workforce shortage that's impacting thousands of Minnesotans at a critical point in our fight against the pandemic. Right now, emergency room patients can't be moved to a hospital room because there aren't enough employees available to open more beds. People waiting to be discharged from a hospital or otherwise needing long-term care can't access such care because there aren't enough staff to take care of them. People with disabilities struggle to find caregivers to provide the assistance and support they need to live in the community. With nearly 40,000 vacancies, unfilled health care positions account for nearly one in every five job vacancies in Minnesota. But it's not just today's health care workforce we need to be concerned about – Minnesota is projected to add nearly 60,000 new health care jobs over the next decade.

During the pandemic, Governor Walz has brought state agencies together to rally resources and address the shortage – through immediate emergency measures and efforts to recruit and train additional health care workers in the coming weeks and months. As part of these efforts, the Governor proclaimed January 2022 as Health Care Month to raise awareness about the many employment opportunities in health care and encourage more Minnesotans to join in this noble, lifesaving work.

This article takes a deep dive on a multitude of issues leading to and resulting from the health care crisis, highlights particular recruitment efforts and offers suggestions for some ways to address the critical health care workforce shortage now and into the future.

In the September 2020 issue of Minnesota Economic Trends, we presented an article examining some of the immediate impacts of COVID-19 on the Health Care industry. Many of our assessments of industry changes were correct, many challenges remain, and even more have emerged. Our original article focused on the demand side of the workforce, primarily viewing the situation from the industry's perspective. But the most consequential workforce fallout from the pandemic, and the public's response to the pandemic, has instead been on the supply side.

The biggest health care workforce issues were not the transitory changes, such as mass layoffs of dental hygienists for the first time in history; the existing and short-term bottlenecks in education, testing and hiring; or the more enduring changes that were first implemented as emergency measures in the pandemic, such as more widespread use of telemedicine in mental health.

Instead, one of the main concerns at health care employers, industry associations, higher education and other training institutions, and state agencies including DEED and HealthForce Minnesota is how we are burning out and burning through our most valuable resource: our human resource! By many measures, Health Care is facing a workforce crisis, made worse by the ongoing pandemic and waves of new variants.

The upheaval of the COVID-19 pandemic has stretched far and wide across the economy, but no industry has been as directly impacted as Health Care & Social Assistance. From February to April of 2020, total employment in Minnesota fell by 386,000 jobs, or -13.1%, not seasonally adjusted. Though it suffered declines, the Health Care & Social Assistance sector proved more resilient at the outset, dropping by -9.3% over the same period, a loss of 45,315 jobs.

The industry's ability to adjust to challenges is due in part to the essential role that health care plays in the fight against the virus, and our state's health care workers have performed heroically over the course of two long years. Unfortunately with the new and more contagious Omicron variant spreading across the state and making more residents sick again, the industry that has done so well to take care of people throughout this pandemic is also showing signs of illness – and fatigue.

Through a labor market lens, the road to recovery has been rougher in Health Care & Social Assistance than some other industries. By November of 2021, Minnesota was down just 42,000 jobs compared to February of 2020, reaching 98.6% of pre-pandemic employment levels; while Health Care & Social Assistance was still down 24,500 jobs, back to just 94.9% of February's peak.

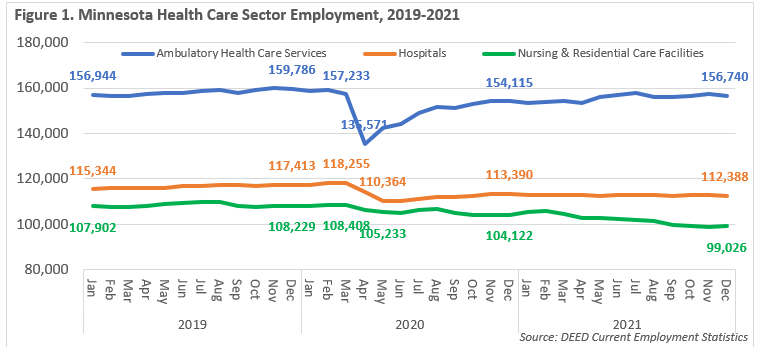

The initial shock was felt most acutely in Ambulatory Health Care Services, which includes Offices of Dentists & Other Health Practitioners that were shut down initially, while Hospitals also cut jobs as they put off elective surgeries gearing up for the unknown strains of a pandemic. Both bounced back quickly and by August of 2020, had started to see a steady return of laid off workers returning to work. After gaining more than 3,000 jobs over the year, Ambulatory Health Care Services is now back to 99% of pre-pandemic employment levels. Employment was stable at Hospitals this year and was back to 95.5% of February 2020 job counts.

In contrast, Nursing & Residential Care Facilities saw the smallest decline from March to May of 2020, but have started to hemorrhage jobs as the pandemic has dragged on. After climbing back to just under 106,000 jobs in February of 2021 – one year from the start of the pandemic – Nursing & Residential Care Facilities have now lost nearly 9,500 jobs through November of 2021, an almost -9% drop compared to February of 2020. By this measure, the long-term care industry is in crisis (see Figure 1). This loss of jobs is due to closures as well as workers exiting to other opportunities or into retirement, and then a lack of new workers to refill them; the industry estimated it has 23,000 - 25,000 open positions in January 2022.

At the center of the fight against the virus, workers in the Health Care sector have repeatedly answered the call to work under continued stress. The pressure has almost certainly taken its toll on health care workers, leading to a record number of openings both from increased demand and the need to replace workers who have retired or otherwise left the industry. This is especially true in the long-term care sector, where thousands of workers have exited the labor force.

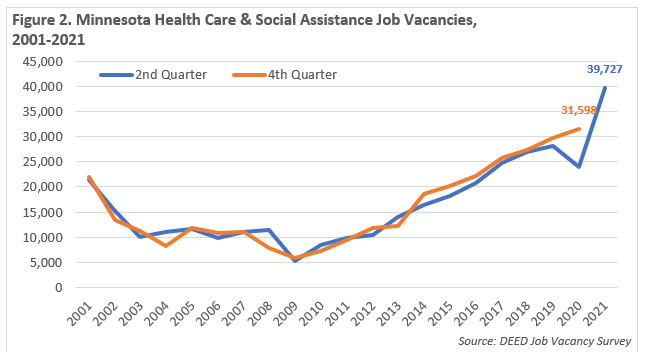

As of the second quarter of 2021, there were nearly 40,000 Health Care & Social Assistance job vacancies in Minnesota, accounting for about one in every five vacancies in the state. This is the largest number of vacancies ever reported, surpassing the peak set in the fourth quarter of 2020. By that measure, demand for health care workers has never been higher in the state (see Figure 2).

This includes more than 9,250 openings for Home Health & Personal Care Aides, just over 6,000 vacancies for Certified Nursing Assistants (CNAs), nearly 4,800 Registered Nurses (RNs) postings, 2,400 jobs for Licensed Practical Nurses (LPNs), 860 openings for Medical Assistants, and about 700 postings for Clinical and Laboratory Technologists and Technicians. In each case except Medical Assistants, these are new record highs. Demand is also up for Building & Grounds Cleaning and Maintenance, Food Preparation & Serving related, and Office & Administrative Support occupations, all of which represent many positions in health care settings.

There are many barriers to drawing in new workers, but there are also examples of new ideas that are having success. To meet the immediate need in late 2022, Governor Tim Walz deployed the National Guard to be trained and work as CNAs in skilled nursing facilities in crisis. By December 9, Minnesota State Colleges had fully trained 298 Minnesota National Guard Members to be CNAs, and an additional 212 had started training. This is even more remarkable given the speed at which the training was done - instructors taught the 75-hour course in about eight days. It was certainly a challenge for instructors and students, but most found the experience very rewarding. State Nursing Assistant Competency Exam results were impressive: all but two National Guard trainees passed on the first try and the remaining two passed with a retake.

In addition, as one of the highest profile, highest need occupations, the state of Minnesota has changed its approach to recruiting more CNAs by making the training free. The Next Generation Nursing Assistant initiative has set a goal to recruit at least 1,000 new CNAs and train them for employment in Minnesota long-term care facilities experiencing staffing shortages as soon as possible.

"Prior to our Governor's announcement, Nursing Assistant program directors had been telling me they had ample training capacity, they just could not get any students. In the summer of 2021, one director told me that even though the economics were not favorable for her college she would run a class with just five students, but she couldn't even get five students," according to Anthony Schaffhauser, the Director of Healthcare Workforce Development at HealthForce Minnesota. "Now with promoting 'free', classes are filling and there are waitlists. Remove any hint of a cost barrier and the classes suddenly fill. It is working even better than we ever would have expected!"

This is not the first time or the only path to free CNA classes – many skilled nursing facilities can provide this training to their employees and eligible CareerForce customers can access free training. Likewise, the Department of Human Services' SNAP Employment & Training program could also cover costs; but the intake forms, requirements, and reimbursement timeframes can pose a barrier. Making the CNA training both free AND easy has seemingly improved the effectiveness of the programs.

The results have been encouraging - as of January 26, 2022, 558 students had been enrolled, and an additional 267 spots in scheduled CNA classes were available. In addition, 338 Minnesota high school students are enrolled in CNA training through their schools and slated to complete training by the end of the school year. Grants are also now available to expand CNA training programs at Minnesota high schools and get more students into the pipeline.

"In addition to CNA, we should also make Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) training free. These are the two basic 'first rungs on the ladder' of healthcare careers, and they appeal to different personality types," added Schaffhauser. "From this initial job, employees can advance on to essentially any career ladder in health care. One director told me just yesterday that they have a Next Generation CNA student who wishes to become a physician."

The unprecedented number of health care openings and new ways to access training for an entry point into health care represent an abundance of opportunities for jobseekers that have a desire for a meaningful career and a chance to take care of other people and make a difference in their lives, including many that historically have been less represented in the healthcare workforce.

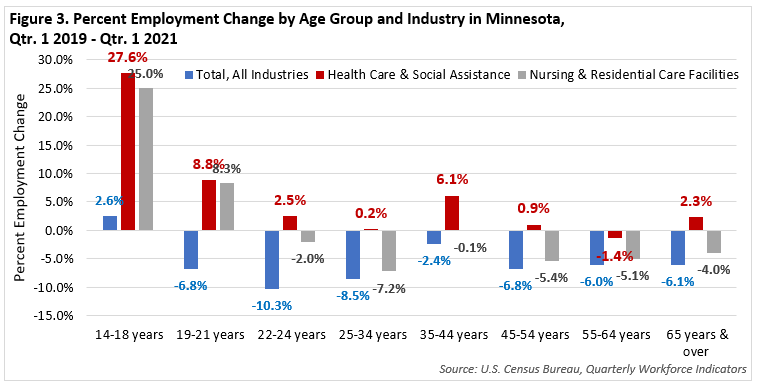

The Health Care & Social Assistance workforce has become more diverse over time, both by age and race. Since the pandemic started, the percentage of males making up the Health Care & Social Assistance workforce has also grown slightly from 22.4% in 2019 to 23.4% in 2021. Much like the population, the workforce is getting older, with big shifts ushered in by the baby boom generation. Since 2010, the number of Health Care & Social Assistance jobs held by workers aged 55 years and over increased by 42% – twice as fast as industry growth overall. By 2019, workers in these oldest age groups accounted for 23.2% of total workforce, nearly equal to the share of workers between 25 and 34 years of age, and between 35 and 44 years of age. The share of workers that were 24 years or younger remained at 12% over the course of the decade, while both the number and share of workers from 45 to 54 years of age dropped as Baby Boomers moved through the population pyramid.

Trends were similar, but more severe, in the Nursing & Residential Care Facilities sector, which added older workers, lost 45 to 54-year-olds, but relied on the youngest workers for 20% of jobs – a significantly higher percentage than Health Care overall. From 2010 to 2019, the Nursing & Residential Care sector added 1,200 new jobs for teenagers and young adults; but gained more than 7,250 workers aged 55 years and over as the workforce aged.

With COVID concerns, child care challenges, and falling labor force participation rates, this dynamic shifted over the past two years. Young people have stepped up and taken more jobs, especially in Health Care & Social Assistance. The percent of Health Care jobs held by 14 to 18-year-olds went from 1.7% in 2019 to 2.1% in 2021, or from about 8,500 jobs in the first quarter of 2019 to 10,800 jobs in the first quarter of 2021 – a rapid increase, but only 2,300 net new jobs. Likewise, 19 to 21-year-olds took an additional 1,800 jobs over the past two years as employers scrambled to fill positions. In contrast, the number of jobs held by workers aged 55 years and over dropped since 2019 (see Figure 3).

While Ambulatory Health Care Services and Hospitals had the benefit of a stronger bounce back, Nursing & Residential Care Facilities lost workers in every age group above 25 years of age. Thankfully, young workers answered the call and took on nearly 1,900 additional jobs, but the sector still needs more new workers. Long-term care facilities lost older workers at a staggering rate, but perhaps most surprisingly, the biggest and fastest loss occurred in workers from 25 to 34 years of age, including those with kids at home. The work is taxing physically and emotionally, many facilities are understaffed, and the providers are desperate for workers. That's a difficult situation for everyone involved (see Table 1).

| - | 14-18 years | 19-21 years | 22-24 years | 25-34 years | 35-44 years | 45-54 years | 55-64 years | 65 years & over |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qtr. 1 2019 | 4,572 | 9,160 | 9,191 | 26,041 | 21,894 | 19,278 | 19,904 | 6,695 |

| Qtr. 1 2020 | 4,825 | 9,311 | 8,849 | 25,082 | 22,257 | 18,831 | 19,783 | 7,002 |

| Qtr. 1 2021 | 5,714 | 9,916 | 9,010 | 24,159 | 21,862 | 18,230 | 18,892 | 6,426 |

| 2019-2021 | +1,142 | +756 | -181 | -1,882 | -32 | -1,048 | -1,012 | -269 |

| Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Quarterly Workforce Indicators | ||||||||

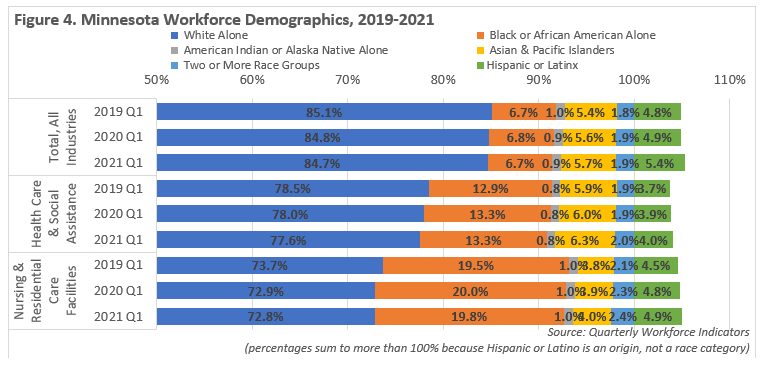

The Health Care & Social Assistance industry already had one of the more racially diverse workforces in the state, but during the past decade it rapidly became more diverse. From 2010 to 2019, the number of jobs held by Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) increased more than 82%, nearly four times as fast as the industry overall. BIPOC workers accounted for nearly two-thirds of the jobs added over the decade.

For context, people who identified as White Alone held 85% of jobs across the total of all industries in 2019, which was down from 89.5% in 2010 as the state's BIPOC population and workforce continued to grow. However, people who identified as White Alone held 85% of Health Care & Social Assistance jobs in 2010, and by 2019 that percentage had dropped to 78.4% of jobs in the industry. In 2019, 13% of Health Care & Social Assistance jobs were held by Black or African Americans, 6% were held by Asians or Other Pacific Islanders, and 3.8% were held by Hispanic or Latinx people. Nursing & Residential Care Facilities were the most racially diverse sector, with about 73% of workers reporting white Alone as their race, and Black or African Americans accounting for almost 20% of jobs.

Then from the first quarter of 2019 to the first quarter of 2021, Nursing & Residential Care Facilities lost nearly 2,900 workers who identified as White Alone and also saw a net decline of 80 Black or African American jobholders. But the industry saw a bump of nearly 350 additional jobs held by Hispanic or Latinx workers, as well as 284 net new jobs for workers of two or more races and nearly 125 jobs held by Asian or Other Pacific Islanders (see Figure 4).

Foreign-born workers have also been a key source of labor force growth over the past decade, especially in Health Care. After adding more than 80,000 workers between 2010 and 2019, there were nearly 325,000 immigrant workers in the state at the end of the decade according to Census Bureau estimates. Foreign-born workers accounted for about 10.5% of Minnesota's total labor force, but accounted for 47% of the state's labor force growth during the past 10 years. In comparison, the state also gained more than 90,000 U.S.-born workers in the decade, accounting for 89.5% of total workers.

Along with Manufacturing, Health Care & Social Assistance employs the largest number of immigrants. Based on estimates from the American Community Survey and DEED's Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages program, there were around 58,615 foreign-born workers in Health Care & Social Assistance industry in 2019, which was up from about 36,250 in 2010, a gain of more than 22,000 over the decade.

Data on foreign-born workers are not available for 2020 and 2021 yet, but immigrants already have and should continue to provide a vital source of new workers for Health Care employers, and more specifically, Nursing & Residential Care Facilities. Part of DEED's work is making sure that immigrants and refugees have access to training resources to prepare them for critically in-demand health care positions and help them move up the healthcare career ladder.

While the health care workforce is already more diverse than Minnesota's workforce overall, it is still true that we cannot increase the numbers of new nurses without increasing the diversity. Increasing diversity of the nursing workforce would have multiple benefits.

Bob Muster, an academic Dean at our State Colleges, informed us about the barriers to increasing the diversity of our nursing profession: "My(personal) take on it (again, personal, not "correct") is that the admissions criteria are designed to admit only those with a proven track record in succeeding in an educational system designed by and for the dominant culture. This design and implementation perpetuate the structural racism with which we are currently faced. The overwhelming whiteness of the nursing workforce creates measurably disparate health outcomes for BIPOC patients."

HealthForce Minnesota sees a great opportunity for nursing programs to facilitate the student development of those who have the disposition to be a nurse to achieve the academic skills to be a nurse. There are some promising models.

Even if the state was able to expand and diversify the nursing student population, we would also need to recruit more nursing instructors. According to HealthForce, a long-standing problem remains the lack of faculty. Job Vacancy Survey results showed more than 325 openings for postsecondary teachers in health science-related programs, including a record number of openings for Health Specialties Instructors.

While teaching has its own inherent rewards, the salary disparity between what instructors earn and what practicing workers earn makes it difficult to recruit faculty. DEED's Occupational Employment & Wage Statistics show that the difference in median wage between RNs and postsecondary nursing instructors is about 12% - $81,154 versus $72,696. However, nursing faculty would likely need at least a master's degree, and many instructors even have a Doctorate. They also have a lot of valuable experience, which makes the comparison to Nurse Practitioners (NP) more applicable in many cases, especially when one considers nursing graduate programs. The difference in salary between NPs and nursing instructors is closer to 70% (see Table 2).

| SOC Code | SOC Occupational Title | Estimated Statewide Employment | 25th Percentile Wage | Median Annual Wage | 75th Percentile Wage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 000000 | Total, All Occupations | 2,708,760 | $32,837 | $47,832 | $73,149 |

| 251042 | Biological Science Teachers, Postsecondary | 890 | $62,289 | $78,695 | $101,876 |

| 251066 | Psychology Teachers, Postsecondary | 790 | $62,452 | $79,460 | $101,815 |

| 251071 | Health Specialties Teachers, Postsecondary* | 3,270 | $64,278 | $101,101 | $168,276 |

| 251072 | Nursing Instructors & Teachers, Postsecondary | 1,280 | $48,403 | $72,696 | $91,245 |

| 291141 | Registered Nurses | 70,820 | $69,053 | $81,154 | $97,244 |

| 119111 | Medical & Health Services Managers | 8,070 | $81,393 | $102,712 | $130,898 |

| 291171 | Nurse Practitioners | 4,080 | $110,242 | $123,312 | $135,515 |

| 291071 | Physician Assistants | 2,570 | $112,028 | $125,894 | $139,861 |

| Source: DEED Occupational Employment & Wage Statistics *wage data for the U.S. |

|||||

According to a September 2020 Fact Sheet on the Nursing Faculty Shortage from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), "U.S. nursing schools turned away 80,407 qualified applicants from baccalaureate and graduate nursing programs in 2019 due to insufficient number of faculty, clinical sites, classroom space, and clinical preceptors, as well as budget constraints. Almost two-thirds of the nursing schools responding to the survey pointed to a shortage of faculty and/or clinical preceptors as a reason for not accepting all qualified applicants into their programs." However, there is some hope in more recent education statistics. An April 2021 report from the AACN showed that enrollment jumped 5.6% year-over-year in 2020 for bachelor's and graduate nursing programs, despite challenges presented by the pandemic.

It would likely not be possible for higher education to increase nursing faculty wages by 12%, let alone 70%. One idea that HealthForce Minnesota has proposed would be to ask our health provider systems to fund "joint appointments" where their nursing employees could teach for the colleges and universities, with the colleges and universities paying their typical wage, and then industry partners making up the balance.

In theory, this could provide benefits to everyone involved. Already facing huge losses of nurses, offering a sabbatical to teach for a year or two might enable employers to retain them. Health care systems might also enjoy priority access to recruit from the classes where their instructors would be embedded with their future workforce. Many providers are spending large amounts on recruitment, onboarding, and travel nurses to combat the attrition, so this may provide a better cost-benefit equation.

Most health care systems also have foundations, which might be another option for funding the program. If a positive return on investment can be proven, the best instructors could be given a provider-endowed faculty appointment to continue to teach for their now-extended careers and continue to build a strong pipeline for students to become workers.

Laura Beeth is the Vice President of Talent Acquisition at M Health Fairview, the Chair of HealthForce Minnesota's Healthcare Education Industry Partnership (HEIP) Council, and a longtime member and Chair of the Governor's Workforce Development Board. In response to the workforce crisis, Beeth shares a new mantra in health care providers' human resources departments: "You take care of others and their families, let us help take care of you and yours."

In a recent Health Care Workforce Roundtable hosted by the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development, Beeth described the efforts now made to retain their workforce: "Would you stay if we changed your shift? Would you stay if you moved to a different position? We have actually reached out to every person that left our organization to come back." Beeth also noted that the support for employees to continue their education and "earn while they learn" has never been greater in her entire career.

Jessica Miller, a DEED Workforce Strategy Consultant, presented ideas and discussed best practices with attendees of a series of Workforce Summits that were convened by Care Providers of Minnesota. The discussions were about what the attendees could do right now, leaving post-stabilization discussion for a future summit.

Miller advised attendees to work on their brand and know the "word on the street" about their facility. This includes using testimonials from current employees who have grown and enjoy a rewarding career, followed up with a concrete recruiting action plan, keeping in mind that "Recruiting is about what you can do, not what you can't do." Miller also emphasized that the real solution is in employee retention.

The theme to support employees was front and center. As an example, Miller shared a story about how "Lakeview Methodist in Fairmont partnered with a childcare provider to offer care to their employees and to the community. They rent them space in their facility that was going unused, and the childcare provider pays them rent and utilizes their food service. The residents can interact with the children within infection control protocols, and the childcare facility pays less overall then if they were on their own."

DEED has a growing and on-going series of online webinars exploring more examples of successful recruiting and retention strategies.

Job seekers entering the health care field can expect a level of job security commensurate with their dedication to care. Data show that younger and more diverse workers have taken notice, seizing opportunities at higher rates than other worker groups over the past two years. There are many openings in health care employment now – at every level, in every part of Minnesota and in every setting.

Many entry-level health care positions can be started with employer-provided training and many of those positions can leverage skills and experience from other industries, meaning people with employment experience from other sectors are encouraged to apply.

Wages go up with additional training and certification, which in some cases is also paid for by the employer. Many positions pay significantly more than they did a year ago. For example: The average wage for workers in Nursing & Residential Care Facilities, at $21.13 in December 2021, rose 12.4% over the year.

There is projected long-term demand for many health care positions, according to DEED's Labor Market Information office, as well as critically high current demand for many health care workers. There are projected to be another 59,815 new health care jobs in Minnesota over the next decade, a 12.6% increase.

| NAICS Code | Industry | Estimated Employment 2020 | Projected Employment 2030 | Percent Change 2020-2030 | Numeric Change 2020-2030 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Total, All Industries | 2,975,300 | 3,145,200 | +5.7% | +169,900 |

| 62 | Health Care & Social Assistance | 473,914 | 533,729 | +12.6% | +59,815 |

| 621 |

Ambulatory Health Care Services |

149,371 | 169,204 | +13.3% | +19,833 |

| 6211 |

Offices of Physicians |

70,904 | 75,966 | +7.1% | +5,062 |

| 6212 |

Offices of Dentists |

15,188 | 16,290 | +7.3% | +1,102 |

| 6213 |

Offices of Other Health Practitioners |

16,582 | 20,731 | +25.0% | +4,149 |

| 6214 |

Outpatient Care Centers |

11,308 | 13,292 | +17.5% | +1,984 |

| 6215 |

Medical & Diagnostic Laboratories |

3,070 | 3,717 | +21.1% | +647 |

| 6216 |

Home Health Care Services |

25,496 | 30,975 | +21.5% | +5,479 |

| 6219 |

Other Ambulatory Health Care Services |

6,823 | 8,233 | +20.7% | +1,410 |

| 622 |

Hospitals |

121,937 | 129,836 | +6.5% | +7,899 |

| 623 |

Nursing & Residential Care Facilities |

106,356 | 112,574 | +5.8% | +6,218 |

| 6231 |

Nursing Care Facilities |

40,818 | 40,134 | -1.7% | -684 |

| 6232 |

Residential Mental Health Facilities |

29,727 | 31,153 | +4.8% | +1,426 |

| 6233 |

Community Care Facilities for the Elderly |

25,286 | 30,258 | +19.7% | +4,972 |

| 6239 |

Other Residential Care Facilities |

10,525 | 11,029 | +4.8% | +504 |

| Source: DEED Employment Projections | |||||

The only health care sector that is not expected to show job growth is Nursing & Residential Care Facilities, which has also been struggling to deal with changing demand, workforce shortages, and higher turnover. Schaffhauser explained how "the pandemic caused a negative feedback loop where a lack of CNAs to work needed shifts, often due to employee COVID exposures or infections, meant that the remaining CNAs had to work double shifts. One will only abandon one's family for so long before they say "enough, I quit," making a worsening situation a dire situation."

Rising wages and countless job opportunities in other industries, even including typically low-paying industries like Retail Trade and Leisure & Hospitality, gave these CNAs lots of other options that they may not have been interested in previously. This changed labor market landscape has given CNAs and other low-wage healthcare support workers more power in the job market, which long-term care facilities have traditionally been less able to react to because of constraints on the ability to rapidly or significantly increase wages.

Even though the Next Generation Nursing Assistant initiative is working to quickly enroll students, Schaffhauser notes that "it is still rescue and triage. While 1,000 additional nursing assistants is impressive, the immediate need is perhaps seven times higher due to turnover. Based on personal communications with contacts at long-term care facilities, I've heard a working estimate of 300% annual turnover."

While it does not show a turnover rate nearly that high, turnover data from the Quarterly Workforce Indicators does highlight how turnover is a significant issue for Nursing & Residential Care Facilities. The stable turnover rate, which measures the number of hires and separations across quarters in comparison to full-quarter employment, has been nearly twice as high in Nursing & Residential Care Facilities as in Ambulatory Health Care Services and Hospitals over the past year, and were also well above the total of all industries (see Table 4).

| - | 2020 Q1 | 2020 Q2 | 2020 Q3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total, All Industries | 8.9% | 7.9% | 8.5% |

| Health Care & Social Assistance | 8.6% | 8.9% | 7.3% |

|

Ambulatory Health Care Services |

7.2% | 7.3% | 6.6% |

|

Hospitals |

5.0% | 7.0% | 3.8% |

| Nursing & Residential Care Facilities | 11.4% | 11.4% | 10.8% |

| Source: Census Bureau Quarterly Workforce Indicators | |||

In addition to the turnover issues and increased burnout of remaining workers, insufficient staffing at long-term care facilities also complicates the rest of the health care system. Without available beds on long-term care, Hospitals are not able to provide a safe discharge, leading to patients staying in the hospital for observation at a higher cost, and creating additional stresses at the Hospitals as well.

"We need to look very carefully about prioritizing the whole health care continuum because when we're broke, it ripples to everyone," said Patti Cullen, president and CEO of Care Providers of Minnesota on the January health care workforce roundtable. "The greatest needs are just about every position. Of the (Health Care) 40,000 openings we know at least about 23,000 to 25,000 are in long-term care."

The health care workforce crisis is acute now, particularly in long-term care, but it risks becoming a chronic problem unless we make big changes. At a time when so many people are reconsidering their options in a dynamic economy, we need to continue to reinforce the message that choosing a career path in health care is full of purpose and potential. State agency and office leaders, HealthForce Minnesota, will continue to collaborate with health care industry leaders, explore options and push for solutions to help address Minnesota's current health care workforce crisis and put structures in place to build a stronger pipeline for health care workers for the future.

About the authors:

Anthony Schaffhauser is the Statewide Director of Healthcare Workforce Development for HealthForce Minnesota, which is a Minnesota State Colleges and Universities Center of Excellence that inspires students, enhances education, and engages industry in order to closely collaborate and innovate with key stakeholders to develop Minnesota's current and future healthcare workers. Our vision is that Minnesota's full range of healthcare needs are well-served by the nation's best healthcare workforce: dedicated, diverse, compassionate, and highly qualified.

Cameron Macht is the Regional Analysis and Outreach Manager for the Minnesota Department of Employment & Economic Development (DEED), supervising a team of regional analysts that provide labor market information to support workforce and economic development efforts across the state, as well as a team of analysts at DEED headquarters providing tools and research.