by Alessia Leibert and Teri Fritsma

September 2017

Minnesota is struggling to meet growing demand for mental health workers, particularly in rural parts of the state.

While many people pursue higher education in mental health-related fields like psychology, counseling, social work, and marriage and family therapy, a scarcity of mental health providers throughout Minnesota is raising considerable concern.

Long wait times for clinical appointments and lack of access to mental health specialists—particularly in rural areas of the state—have, in recent years, prompted a variety of studies, task forces and legislative interventions to increase the size of the mental health workforce. Though these efforts have met with some success, they have also highlighted significant challenges around defining and quantifying the state's mental health workforce.

Mental health providers come from at least five different profession types, covering nine different professional licenses that occupy separate but overlapping niches of service.1 As we will see, there is also a large non-licensed contingent of workers in social service industries, making it even more difficult to estimate the supply and demand for mental health workers.

Compared with the straightforward training and licensure requirements for similar health professions such as nursing, pharmacy or dentistry, the mental health workforce includes providers with varying levels of education, licensure, scopes of practice and job requirements. Yet without a way to count them, it is extremely difficult to evaluate whether efforts to grow the mental health workforce are effective.

This article is the first attempt, to our knowledge, to provide a comprehensive investigation into Minnesota's complete mental health workforce. Our goals are to (1) identify and describe the educational pipeline for mental health workers in Minnesota; (2) examine both the licensed and unlicensed workforce in order to determine the extent to which these two groups are occupying a similar niche in the labor market; (3) identify which regions struggle most to attract licensed mental health providers; and (4) discuss potential policy implications of the findings.

Following the federal Health Resource and Services Administration and the Minnesota Legislature,2 this study includes the following groups as part of the mental health workforce:

Licensure in Mental HealthLicensing is intended to protect the public by ensuring that competent and ethical individuals practice in an occupation. State law mandates that individuals must be licensed to provide mental or behavioral health services, with very few exceptions. The four state licensing boards of Psychology, Marriage and Family Therapy, Behavioral Health and Therapy, and Social Work are responsible for establishing and enforcing state laws that govern professional standards in these fields. In practice, however, the distinction between work that requires a license and work that does not is difficult to enforce, especially in human service or social assistance fields that may not involve the provision of mental health services. It is important to note that licensing boards, not employers or workers, ultimately have the authority and responsibility to determine who needs to be licensed. |

Consequently, the formal educational pipeline for mental health workers includes all individuals who pursue training that prepares them for licensure as one of these provider types, regardless of whether they obtain licensure. We include all graduates in this study in order to get a comprehensive picture of those who are likely providing mental or behavioral health and related social services in Minnesota. Only the work of licensed mental health practitioners and professionals, however, is governed by Minnesota law and sanctioned by state licensing boards. As shown in Table 1, Minnesota licensing standards vary widely by profession, with educational requirements ranging from a bachelor's degree to a doctorate.

| Educational Pipeline and Licensure Requirements by Profession Type | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Provider type/Licenses | Educational pipeline | Current education and supervised practice requirements for licensure | Example job titles |

| Mental Health Professionals | |||

| Psychologists (LP) | Doctorate in psychology (except educational psychology) | Doctorate in psychology 1,800 hours of postdoctoral supervised employment in psychology | Clinical or private practice psychologist |

| Social Workers (LICSW) | Graduate degree in social work | Graduate degree in social work 200 hours of direct supervision over 4,000 hours of post-graduate clinical practice. | Clinical social worker; licensed therapist |

| Marriage and Family Therapists (MFT); Licensed Professional Clinical Counselors (LPCC) | Graduate degree in counseling, marriage and family therapy, or a related degree | LMFT: Graduate degree in marriage and family therapy or a related field from an accredited program and 200 hours of direct supervision over 4,000 hours of supervised professional practice.LPCC: Graduate degree in counseling or a related field from an accredited program and 200 hours of direct supervision over 4,000 hours of supervised professional practice. | Marriage and family therapist; licensed mental health counselor; behavior analyst |

| Mental Health Practitioners | |||

| Social Workers (LSW, LISW, LGSW) | Bachelor's or graduate degree in social work, depending on license type | LSW: Bachelor's degree in social work. 4,000 hours of supervised practice is required after the license is issued.LGSW: Graduate degree in social work. 4,000 hours of supervised practice is required after the license is issued.LISW: Graduate degree in social work. Supervised non-clinical practice is required before licensure: 100 hours of direct supervision over 4,000 hours of non-clinical practice. | Caseworker; protective service worker; adoption social worker; mental health practitioner |

| Counselors (LADC, LPC) | Bachelor's or graduate degree in counseling, with emphasis on substance abuse, depending on license type | LADC: Bachelor's degree with at least 18 semester hours of alcohol and drug counseling coursework, and an 880-hour alcohol and drug counseling practicum.LPC: Graduate degree in counseling or a related field from an accredited program and 100 hours of supervision over 2,000 hours of professional practice that occurs either before or after licensure. | Alcohol and drug counselor; substance abuse counselor; correctional counselor; employment counselor |

| 1Sources: Online information and personal conversations with the boards of Psychology, Social Work, Marriage and Family Therapy, and Behavioral Health and Therapy. These requirements are subject to change and only include education and clinical supervision hours. Licensure also requires an examination, and some licenses also require supervised field experience in a graduate program. | |||

Broadly speaking, two factors determine the supply of professional mental health providers: (1) the size of the pipeline and (2) the rate at which graduates become licensed. As of 2015, Minnesota employed an estimated 22,630 workers in mental health-related occupations, including both licensed and non-licensed employees.3 In just nine years—from July 2006 to June 2014—Minnesota colleges and universities produced nearly half that number of graduates (9,851) in the mental health-related programs identified in Table 1.4

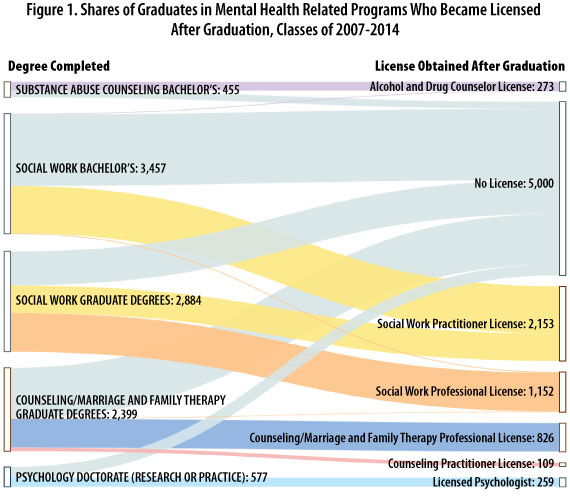

Of these 9,851 Minnesota graduates, only half (49.1 percent) pursued licensure. Figure 1 displays the share of graduates who went from degree to licensure by field of specialization. The likelihood of pursuing a license varies by field. During this period, master's-level graduates of marriage and family therapy as well as counseling programs were the least likely to pursue a license, whereas master's-level graduates in social work were the most likely.

Interestingly, among master's graduates in social work, one out of four decided to obtain a practitioner's license rather than a professional license. In some cases, this could be because master's-level social work graduates have obtained the practitioner license but are still working toward a professional-level license.

In terms of size, the largest pipeline is in social work and the smallest in psychology PhDs. It is important to point out that bachelor's programs in psychology are extremely popular among students. From July 2006 to June 2014, Minnesota colleges produced nearly 14,710 bachelor's graduates in psychology. This large supply, however, either did not continue in school or leaked out to other fields. Only 20—less than 1 percent—completed a doctoral-level credential in psychology.

Table 2 shows how long it took to obtain a license after completing the required degree. Graduate degree holders in counseling, marriage and family therapy, social work, and psychology took between 23 and 37 months on average to complete a license. In contrast, bachelor's graduates in social work and substance abuse/addiction counseling obtained licensure within 19 and 10 months on average, respectively.

| Graduates to License Flows, Classes of 2007-2014 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field and degree level | Total graduates* | Graduates who obtained a license after graduation | Rate of licensure | Average months from degree to licensure |

| Substance Abuse Counseling Bachelor's | 514 | 295 | 57.4% | 10 |

| Social Work Bachelor's | 3,457 | 1,407 | 40.7% | 19 |

| Social Work Graduate Degree | 2,884 | 1,908 | 66.2% | 31 |

| Counseling/Marriage and Family Therapy Graduate Degree | 2,414 | 962 | 39.9% | 37 |

| Psychology Doctorate (research or practice) ** | 582 | 264 | 45.4% | 23 |

| Total | 9,851 | 4,836 | 49.1% | |

| *Includes graduates who had at least one quarter of employment in Minnesota wage records since 2003.

**Note that of the 582 doctorate completers in psychology, 246 completed a research (as opposed to a clinical) track. |

||||

| Source: see "About this Data" for additional data details. | ||||

The pipeline of practitioners is strong because practitioner-level licensure requires far fewer supervised practice hours than professional-level licensure. Obtaining the supervised practice hours can create a significant barrier, because prospective licensees are frequently responsible not only for finding a practicing professional to serve as their supervisor, but often they must pay supervisors for that time directly out of their own pockets.

The low rate of licensure among psychologists raises a special concern. According to the Minnesota Department of Health's 2016 Healthcare Workforce Survey, psychology is demographically the oldest mental health profession, with a median age of 57. Roughly one-quarter of practicing psychologists indicated on the survey that they planned to leave the profession within five years, most to retire. If the graduation and licensing rate of doctoral-level psychologists continues at the meager pace we see here, it will not be enough to fill the need or the demand (which many have argued is already woefully undersupplied).

Among the three types of professional-level licenses—marriage and family therapists, independent clinical social workers and licensed professional clinical counselors (LPCC) —LPCCs are closest to psychologists in terms of the theoretical underpinnings and orientation of their educational coursework. Therefore, they may be best positioned to at least partially fill the gap left by retiring psychologists.5

But while the number of master's-level counselors is more than adequate, their rate of licensure (39.9 percent, combined with marriage and family therapy graduates) is low, and the length of time from graduation to licensure is long. The low rate of licensure in this group might be because the LPCC license itself is new, dating back to 2008. The licensed counseling profession is growing, and we expect the licensure rate will increase over time.

In general, these findings raise concern, but also pinpoint areas of opportunity. We return to this discussion in the final section of this report.

The approximately 5,000 non-licensed mental health graduates pose a puzzle: Are they, in fact, part of the mental health workforce, and should they be factored in to discussions about supply and demand of this critical group of providers?

Recall that people who provide mental health services must be licensed in Minnesota (see sidebar). However, non-licensed mental health program graduates who work in social service-oriented positions take a wide variety of settings and roles, some of which overlap with licensed positions in terms of skill requirements and duties. They may work as life coaches, independent living skills specialists, youth program coordinators, clinic intake coordinators and direct care providers, for example. A key difference between licensed and non-licensed workers is the degree of independent decision-making permitted by Minnesota law. Non-licensed mental health workers can provide direct or "front line" care under supervision, and they are not permitted to diagnose patients or devise treatment plans.

About the DataThis research relies primarily on three data sources: (1) 2016 public licensure data from the four licensing boards that govern the licensure of the mental health workforce: Psychology; Social Work; Marriage and Family Therapy; and Behavioral Health and Therapy; merged with (2) wage record data from DEED and (3) post-secondary graduation records from the Office of Higher Education, which covers for-credit public and private programs of one term or longer in Minnesota. Included in the dataset are 9,851 graduates from 23 institutions in Minnesota, both public and private, who obtained a post-secondary credential from July 2006 to June 2014. Graduates who earned more than one degree in the same academic year were classified according to the highest degree obtained. The dataset used for the labor market outcomes analysis (Figures 2-3 and Table 3) has fewer than 9,851 records because of a few exclusions. Graduates who went to work for the federal government, owned their own small unincorporated business, or left the state are excluded because these workers are not covered by the Minnesota Unemployment Insurance Program. Graduates older than 60 at the time of graduation were excluded because people who are near retirement might skew the results of a study of labor market outcomes. |

Beyond that, however, the distinction between licensed and non-licensed mental health positions can be blurred. Some employers advertise positions open to both licensed and unlicensed applicants. DEED's Job Vacancy Survey shows that only about half of all job openings for positions advertised as mental health counselors or substance abuse counselors required licensure in the 2015-2016 period. Licensure was required for about 70 percent of job openings listed as marriage and family therapists and for 70 to 80 percent of those listed as social work positions.

By contrast, nearly all other job vacancies that involve diagnosing or treating health conditions required licensure. All openings for doctors, physician assistants, dentists, dental hygienists, occupational therapists and speech-language pathologists required licensure. And nearly all vacancies for registered nurses and physical therapists required licensure. While no hospital would consider hiring a non-licensed registered nurse, these findings suggest that some employers view licensed and non-licensed mental health workers as interchangeable.

To better understand the role of non-licensed workers, we examine two questions. First, do non-licensed graduates work in similar industries (settings) as licensed workers? Second, to what extent does licensure bring higher market rewards such as stable employment and higher wages?

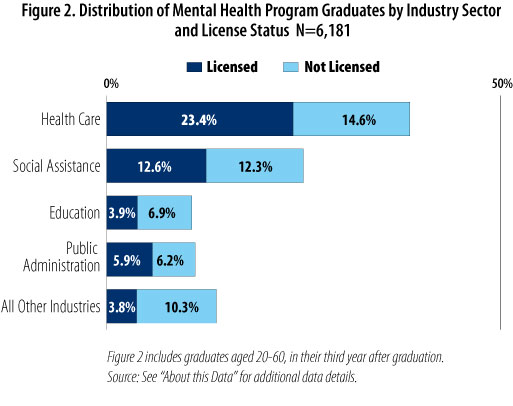

By and large, licensed and non-licensed mental health graduates work in similar industries. Figure 2 displays all mental health program graduates by their industry of employment, and allows us to compare the share of licensed versus non-licensed graduates across various industry settings.

Licensed providers are more likely to be employed in the health care industry compared with their non-licensed counterparts (23.4 percent versus 14.6 percent). They are less likely to be employed in industries other than health care, social assistance, education and public administration (3.8 percent versus 10.3

Overall, though, employment similarities outweigh differences, with the health care sector being the most likely employer and the education sector being the least likely. These findings further support the idea that licensed and unlicensed graduates occupy the same "space" in the market—and that non-licensed employees, while legally barred from performing certain duties, are clearly serving in roles that support and contribute to mental health outcomes in Minnesota.

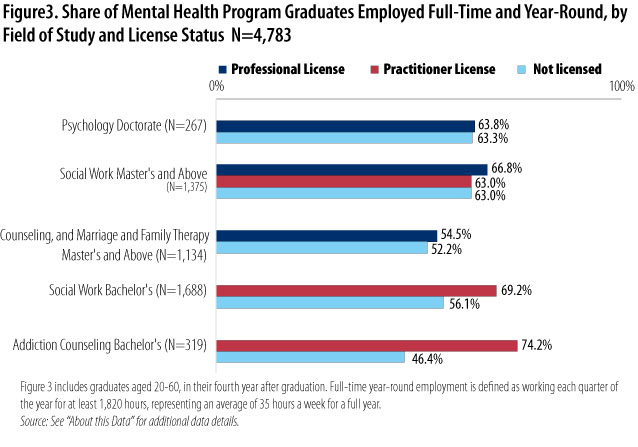

The next question focuses on the market returns associated with licensure. Full-time, year-round employment is an indicator of job quality and stability. As shown in Figure 3, full-time, year-round employment is by no means a given among these recent mental health graduates, particularly among licensed counselors, who have a roughly 54 percent chance of working full-time, year-round.6

Across the board, however, licensed mental health providers have a higher chance of securing stable, full-time employment after graduation compared with others with the same education but no license. In general, licensed social workers and licensed alcohol and drug counselors are most likely to land this type of stable employment.

Even more than job quality and stability, wages are often regarded as the quintessential market reward. Table 3 shows the difference in median hourly wages in the fourth year after graduation for each mental health pipeline group by licensure status and industry (work setting).7

| Median Hourly Wages Earned in Selected Industries, by Field of Study and License Status, Fourth Year After Graduation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | Share of Employment in the Industry | Hourly Wage Not Licensed | Hourly Wage Licensed | License Wage Premium (%) |

| Psychology Doctorate (N=211) | ||||

| Clinics, Including Mental Health | 39.8% | less than 12 | $35.84 | NA |

| Hospitals | 13.7% | less than 12 | $41.68 | NA |

| Social Assistance | 8.1% | less than 12 | $42.60 | NA |

| Education | 15.2% | $26.03 | $29.50 | 13.3% |

| Other Industries | 23.2% | $43.83 | $35.80 | -18.3% |

| Total, All Industries | 100% | $32.21 | $38.33 | 19.0% |

| Social Work Master's and Above (N=1,160) | ||||

| Clinics, Including Mental Health | 20.2% | $23.00 | $24.94 | 8.4% |

| Nursing and Residential Care Facilities | 7.7% | $25.68 | $22.97 | -10.5% |

| Hospitals | 12.6% | $28.28 | $28.89 | 2.2% |

| Social Assistance | 24.7% | $22.98 | $22.89 | -0.4% |

| Public Administration | 15.3% | $26.74 | $27.54 | 3.0% |

| Education* | 13.0% | $26.38 | $30.68 | 16.3% |

| Other Industries | 6.5% | $23.65 | $26.95 | 14.0% |

| Total, All Industries | 100% | $25.31 | $26.25 | 3.7% |

| Counseling and Marriage & Family Therapy Master's and Above (N=1,043) | ||||

| Clinics, Including Mental Health | 27.3% | $20.29 | $25.11 | 23.8% |

| Nursing and Residential Care Facilities | 5.9% | $21.13 | $26.31 | 24.5% |

| Hospitals | 6.0% | $23.12 | $29.45 | 27.4% |

| Social Assistance | 26.2% | $20.06 | $24.24 | 20.8% |

| Public Administration | 5.9% | $26.13 | $27.64 | 5.8% |

| Education* | 13.4% | $24.95 | $24.17 | -3.1% |

| Other Industries | 15.1% | $24.22 | $29.61 | 22.3% |

| Total, All Industries | 100% | $22.28 | $25.60 | 14.9% |

| Social Work Bachelor's (N=1,761) | ||||

| Clinics, Including Mental Health | 9.8% | $17.54 | $19.39 | 10.5% |

| Nursing and Residential Care Facilities | 17.1% | $16.84 | $20.48 | 21.6% |

| Hospitals | 4.4% | $19.50 | $24.91 | 27.8% |

| Social Assistance | 27.7% | $17.12 | $19.17 | 12.0% |

| Public Administration | 15.2% | $21.80 | $23.42 | 7.5% |

| Education* | 7.7% | $17.02 | $24.31 | 42.8% |

| Other Industries | 18.2% | $16.94 | $20.33 | 20.0% |

| Total, All Industries | 100% | $17.64 | $20.86 | 18.3% |

| Addiction Counseling Bachelor's (N=266) | ||||

| Clinics, Including Mental Health | 23.7% | less than 12 | $21.89 | NA |

| Nursing and Residential Care Facilities | 26.7% | $19.21 | $22.59 | 17.6% |

| Hospitals | 16.5% | less than 12 | $22.44 | NA |

| Social Assistance | 10.2% | $17.49 | $22.52 | 28.8% |

| Public Administration | 9.8% | $21.40 | $21.70 | 1.4% |

| Other Industries | 13.2% | $15.72 | less than 12 | NA |

| Total, All Industries | 100% | $19.63 | $22.21 | 13.1% |

| Note: All wage figures have been adjusted for inflation to be in terms of constant 2015 U.S. dollars. | ||||

| *Note that social workers (at both the bachelor's and master's levels) who work in education are most likely to be employed in elementary and secondary schools and counselors are evenly split between elementary/secondary and university-level institutions. Wages are higher for mental health workers in elementary/secondary schools than they are in colleges and universities. | ||||

| Source: The figures presented in this table include graduates who had an employment record in Minnesota in their fourth year after graduation. We limit the display only to graduates ages 20 to 35 because wages for older graduates are more likely to be influenced by work experience than by post-secondary education. Individuals who obtained a license after 45 months from graduation were also excluded because we are unable to determine the impact of licensure on wage results. | ||||

|

See "About this Data" for additional data details. |

||||

Before turning to a discussion of these results, it is important to note that the wage data may exclude some graduates who are working in their own small, unincorporated private practices. This exclusion has the potential to skew results because professionals in private practice are likely earning more than their non-private practice counterparts. Analyses suggest, however, that any bias that exists is minimal.

Overall, 92.4 percent of graduates (four years after graduation) are included in the analysis. Of the 7.6 percent who were excluded, some were excluded because they were no longer in Minnesota or they were not working. An examination of a sample of records showed that most self-employed mental health professionals were identified in DEED wage records and therefore were included in the wage analysis.

There are three main findings to note in Table 3. First, wages generally increase with educational attainment, with the lowest among bachelor's holders and highest among doctorate degree holders.

Second, there is indeed a wage premium associated with licensure. Licensed graduates earn more than non-licensed graduates in every single industry, with only two exceptions—doctorate-level psychology graduates employed in other industries unrelated to mental health, and master's-level social workers who are employed in nursing and residential care facilities.

Third, differences in the distribution of graduates across industries explain some of the differences in earnings across groups. Since wages are almost always highest in hospitals and lowest in social assistance, licensed graduates with lower concentrations in hospitals and higher concentrations in social assistance have lower earnings overall relative to others with the same education level. In particular, mental health counseling professionals have relatively lower wages partially because they can't take advantage of high-paying sectors.

Both wage levels and wage premiums vary substantially by industry setting. Some industries offer both higher wages and a larger wage premium for licensure, while others offer one but not the other advantage. Caution is warranted in interpreting the wage premium results. Premiums ranging from -10 to +10 have to be interpreted as "neutral." Premiums greater than 10 percent indicate license holders earned more than non-license holders among this group of graduates, but we would need a much larger sample to know exactly how much more.

We see the smallest wage premiums in public administration, presumably because these jobs often do not require a license. For example, social work graduates who are county human services workers are not required to be licensed under current state law, though many are licensed voluntarily.

In contrast, some of the largest wage premiums for licensure are in the education sector for social workers. Licensed social workers at the bachelor's and master's level earn approximately 42.8 and 16.3 percent more, respectively, in this sector than their non-licensed counterparts. The health care sector (including clinics, hospitals, and nursing and residential care facilities) presents a mixed picture. The wage premium in hospitals is stronger than in other health care settings, ranging from about 2.2 percent to 27.8 percent, suggesting that licensure is in relatively high demand at hospitals and that licensed workers perform more complex tasks than their non-licensed counterparts.

This is not always the case in clinics and nursing and residential care facilities, where we find no wage premium for licensure at the master's level for social workers, and modest premiums—around 20 percent or less—for other licensed graduates. Such modest wage differentials may not be enough to offset the cost of licensure, especially at the professional level. Even more importantly, wage levels in these two health care sectors are lower than in other industry settings, with the exception of social assistance.

These findings raise questions: Can counseling, marriage and family therapy, and social work graduates access similar types of jobs in clinics and nursing and residential care facilities, regardless of licensure? Lower wage levels and modest wage premiums for licensure among individuals with the same education can cause imbalances in the mental health workforce by discouraging the pursuit of a license in certain segments, or by discouraging employment in the health care sector. Furthermore, if public sector wages for non-licensed individuals are higher than what a licensed individual can make in the health care industry, the incentives to pursue a license will diminish.

Finally, it is important to point out that regardless of pipeline group or licensure status, these wages are below standard compared to others with the same level of education and credentialing required. In 2017, registered nurses (who require an associate degree and license for employment) earned median hourly wages of $36.25. Likewise, occupational, respiratory, speech-language and physical therapists—all licensed occupations requiring comparable amounts of education to mental health professionals—earned median hourly salaries of at least $32. The wages of highly-trained mental health care professionals are closer to those of providers such as licensed practical nurses, respiratory therapy technicians and medical laboratory technicians, all of which require only associate degrees and only one of which requires a license.

Stakeholders have advocated for retention strategies that focus on career laddering opportunities for mental health paraprofessionals. These wage results, however, underscore the challenge for an associate or bachelor's graduate to progress in a mental health career. Without some kind of loan forgiveness program or other incentive, it is hard to imagine how a bachelor's graduate in a mental health program who is already employed could easily afford the cost of a master's degree and licensure.

There are two distinct stories when it comes to the health care workforce: an urban story and a rural one. While health care professionals are generally available and accessible in most metropolitan areas, rural areas consistently struggle to attract health care providers of all types. There are a variety of reasons for this: rural pay is typically lower, there is a smaller recruitment pipeline, and it can be a challenge to attract urban residents to relocate and practice in rural areas.

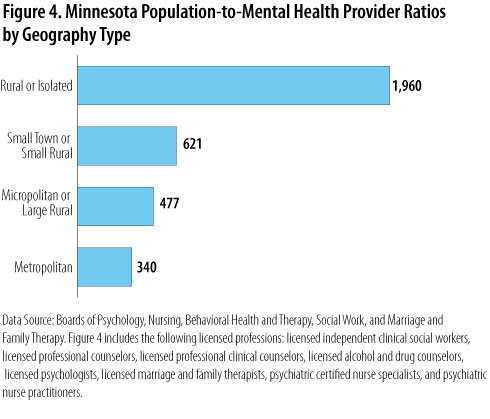

Figure 4 quantifies the urban/rural distribution for licensed mental health providers in Minnesota, and includes all the professions we have studied thus far. Based on data from the four governing health licensing boards, this population-to-provider ratio is a measure of the per capita size of the workforce, or the population that hypothetically "shares" a single provider within an area. Figure 4 shows that there are 340 people to every one licensed mental health provider in metropolitan areas of Minnesota, compared with nearly 2,000 people to every one licensed mental health provider in rural areas.

In response to this problem, public health stakeholders emphasize the importance of developing their own local pipeline. Among other initiatives, these "grow your own" strategies include developing and offering post-secondary programs in rural regions.

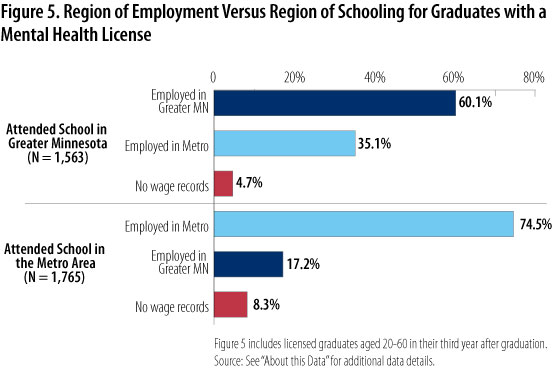

Figure 5 offers some evidence on the likely effectiveness of grow-your-own strategies, showing the employment distribution of those who attended school in the Twin Cities metro versus elsewhere in the state (Greater Minnesota). While the majority (about 74 percent) of mental health students trained in the Twin Cities metropolitan area stay there to work, only about 60 percent of graduates from institutions in Greater Minnesota remain there to work. That is, even given the small share of licensed graduates who attended school at non-Twin Cities institutions (1,765 versus 1,563) Greater Minnesota still loses a higher share of its licensed graduates to Twin Cities employment. This suggests that it will not be enough to simply offer higher education in rural areas. It will also be important to reduce barriers and increase incentives to practice in non-Twin Cities areas, particularly rural areas.

This article identified areas of strength in the mental health educational pipeline and areas of risk.

The first area of strength is the market rewards for licensure. Across the board, licensed mental health providers earn higher wages and have a higher chance of securing stable, full-time employment after graduation compared with others with the same education but no license.

At the same time, even without licensure, graduates in mental health fields find employment in industry settings most highly related to their academic background. Though they cannot legally perform the same scope of work as licensed providers, they should be legitimately counted as part of the mental health workforce.

The second area of potential strength is the popularity of bachelor's programs in psychology and social work. These large programs could sustain future employment growth in the mental health workforce in Minnesota, yet this opportunity is not being leveraged. Only a small fraction of this potential supply goes on to complete graduate training and licensure because of a series of bottlenecks that could be addressed through targeted policies.

Specifically, the findings here lend support to a set of legislative recommendations that resulted from a 2014 mental health workforce task force led by HealthForce Minnesota. Those recommendations included measures to reduce the barriers and burdens associated with clinical and non-clinical supervision, such as creating an institute to provide free supervisor training; creating tax incentives for mental health professionals who offer supervision; and requiring third-party payers to reimburse for the mental health care trainees provide when working under supervision (which they currently do not). Changes such as these would increase the number of working professionals who are willing to offer supervision and potentially reduce or remove the high cost of supervision from students and trainees.

The third area of strength is the expected job growth in mental health careers, especially licensed alcohol and drug counselors, driven by the rising drug epidemic. The data reveal that a bachelor's degree in addiction counseling coupled with an LADC license is a very marketable combination, and these workers are likely to end up in stable, full-time, well-paying positions relative to other mental health bachelor's completers.

There are also areas of specific concern. Even though licensure requires a significant investment of time and money, licensed workers sometimes compete in the market with non-licensed workers with similar levels of training. In some industry sectors, such as nursing and residential care facilities, the wage premium is modest. And regardless of license status, earnings among newly trained mental health individuals are definitely below standard compared with typical wages earned by workers in other health care occupations requiring comparable schooling.

From the perspective of an individual who is making career choices, this certainly reduces the incentive to pursue a professional-level career in mental health. That, in turn, threatens the adequacy and quality of Minnesota's mental health workforce.

Another special area of concern is rural practice. All else being equal, rural providers would have client caseloads of roughly five times the number in urban areas. While offering post-secondary training in Greater Minnesota and rural areas is somewhat effective, Twin Cities employment exerts a strong pull. Just under half of mental health providers educated in Greater Minnesota come to work in the Twin Cities. This suggests that for grow-your-own efforts to be most successful, postsecondary programs in rural areas should be coupled with aggressive efforts to retain workers.

Some rural areas have had success with reaching out to middle school students to get them interested in health careers and with offering health care internship opportunities to college-age students as a way of connecting them to local employers and keeping them tied to the region. The data presented here suggest that creative strategies such as these will be important to retain a strong workforce outside of the Twin Cities.

More broadly, these findings reflect a problem of a higher order: a devaluing of the work of mental health professionals and practitioners. In no other segment of the health care workforce would licensed workers compete for jobs with non-licensed workers, or earn similar wages even though the level of investment, training and competency was far higher. Simply put, hospitals do not hire non-licensed nurses or doctors, and clinics do not hire non-licensed physical, occupational or respiratory therapists.

On-the-job training is also often less structured in mental health than in other health care occupations, leaving it to students to finance their own on-the-job training on top of their formal academic education. We must ask why standards for mental health care are looser, why the line between licensed and non-licensed work is not brighter, and why these professionals are not valued, supported in their training, or compensated to a level commensurate with their preparation.

A common policy solution to health care workforce shortages is to create new professions with lower levels of education and narrower scopes of practice that can assume some of the duties of the shortage profession. Examples include physician assistants to supplement the physician workforce, and dental therapists to supplement the dentist workforce.

These strategies have been successful in other fields, but the findings here caution against such initiatives in mental health. Such a short-term fix will exacerbate the underlying problem in the long run. There are already thousands of non-licensed workers providing services related to mental health and social service. If licensed mental health professionals are not already established as an integral, well-respected and well-compensated part of the health care team, then a strategic policy of hiring more paraprofessionals will only de-professionalize and further depress wages for the licensed workforce. Instead, long-term strategies should emphasize and preserve the importance of high-quality credentialing and standards for this critically important workforce.

It is clear that the need for highly-trained mental health workers will only increase with our population. This research has contributed to our understanding of how to enumerate, support and grow this important group of workers.

1For the purposes of this research, we exclude advanced practice psychiatric nurses and psychiatrists.

2Minn. Stat. 245.462 subd. 16-17.

3This includes DEED's 2016 Occupational Employment Statistics counts for psychologists, substance abuse and other types of mental health counselors, marriage and family therapists, and four classifications of social workers. It excludes psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses.

4A few educational programs were excluded from this count of graduates because they are not designed to prepare for licensure or for employment in a mental health-related field: educational psychology, vocational rehabilitation counseling, and master's and post-master's psychology programs except those in counseling psychology specifically geared toward licensure.

5It is important to note that all three professional-level mental health licenses require nearly identical levels of education, clinical supervision hours and licensure examination. Therefore, though they might have slightly different clinical orientations and foci, these three groups are equally qualified to provide mental health services.

6By way of comparison, national data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that about 17 percent of all adults age 25 and older worked part-time for any reason in 2016. (Among only women, that share was 27 percent.)

7Tracking wages in the fourth year allows enough time for graduates to fulfill the practicum requirements.