by Luke Greiner and Cameron Macht

September 2024

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a powerful tool that is revolutionizing how work gets done, which creates concern for its impact on jobs and the people who hold them. While some predict that AI will lead to increased efficiency, innovation and the creation of new jobs, others fear widespread job displacement and economic inequality. In this complex environment, better understanding AI's potential effects on Minnesota's economy is crucial for businesses and workers, as well as workforce development, economic development, policymakers, educators, and students.

Despite the uncertainty, one thing most observers can agree on: AI will change industries and the occupations within them – and change work duties for many employees to some degree. What is not so clear is exactly how they will change. Hundreds of research reports and articles have been written about AI, with varying levels of insight, optimism, and concern. As we navigate this technological shift, the challenge lies not just in harnessing AI's potential, but in ensuring that the benefits are broadly shared while mitigating the risks of economic disruption.

As AI technologies continue to evolve, their influence on our state's economy will become increasingly significant. Unlike most past waves of technology and automation that have primarily affected blue-collar work, research shows that white-collar work is most susceptible to changes due to AI. In Minnesota, this shift is particularly noteworthy given the state's diversified economy, which boasts a higher-than-average concentration of employment in industries such as Management of Companies, Manufacturing, Finance & Insurance, Health Care & Social Assistance, and Wholesale Trade, all of which will benefit from AI.

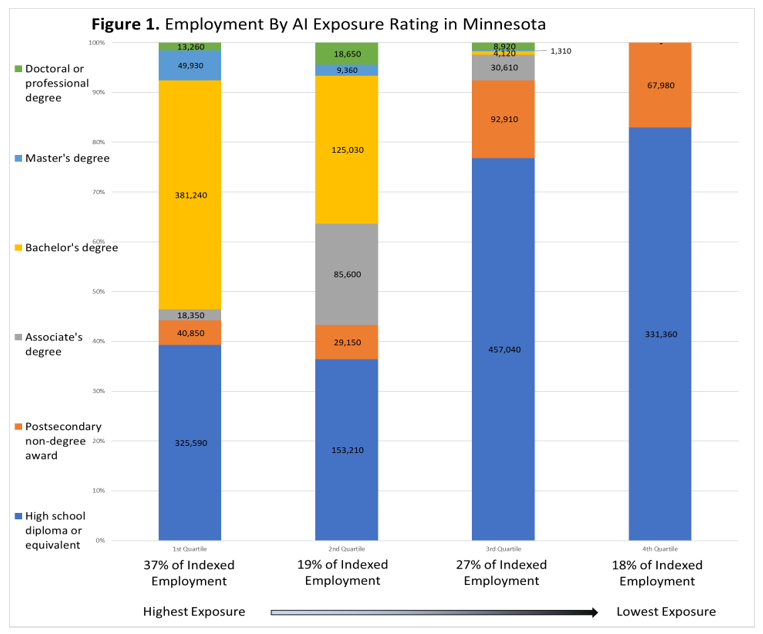

As we'll describe in greater detail in this article, by using quartiles to group the exposure of AI for more than 650 occupations, we try to provide the scope of potential impact in the state. Occupations within the top quartile of highest exposure to AI account for 37% of Minnesota's employment, which would equate to more than 1,065,000 jobs. In sum, employment in Minnesota is skewed towards being more exposed to AI, with 56% of overall employment – or more than 1.6 million jobs across the entire state economy – in the higher exposure quartiles, compared to 44% in the bottom two quartiles.

To be clear, exposure is not defined as positive or negative, nor does it imply replacement over augmentation. For example, AI can help a labor market analyst by providing research assistance, similar to how the spreadsheet allowed the by-hand bookkeeper of the early 1980s to upskill and provide what-if scenarios. In fact, AI was leveraged by the authors of this very article! Yet it is not currently possible for AI to completely replace such tasks, let alone the entire suite of responsibilities in our position, or in writing this article. Even modest AI use requires extensive knowledge to "coach" and refine contributions.

How AI is deployed in individual settings will likely determine if the exposure is positive or negative. To further this example, while we might love to enlist AI to complete the most tedious and time-consuming tasks in our jobs, our counterparts might find enjoyment completing those same tasks and lose job satisfaction without them. AI has already started to impact our jobs as analysts; how much they change is yet to be seen. To that end, exposure is more tangible and reasonable to use for guiding policy and funding mechanisms than reaching for the unknown impact that AI will have in the future.

From our analysis, 56% of indexed occupations in Minnesota have a higher exposure to AI, which would equate to more than 1.6 million jobs across the entire state economy (if all occupations are considered). On one hand, this concentration could provide Minnesota with a competitive advantage, as businesses that effectively integrate AI into their operations could lead the way in innovation, productivity, and economic growth. On the other hand, the same industries that stand to benefit the most are also at higher risk of disruption. White-collar workers in roles traditionally considered stable may find themselves vulnerable as AI systems begin to take on tasks that require cognitive skills, such as decision-making and problem-solving—areas once thought to be the exclusive domain of human workers.

This dual reality highlights the importance of understanding the exposure of Minnesota jobs to AI to help prepare for AI's impact on the state's economy. Figure 1 shows estimates of current employment in selected occupations by exposure to AI, with over half having a higher likelihood. While Minnesota's diversified economy positions us well to leverage AI for growth, it also necessitates strategic planning to ensure that the transition is smooth and inclusive. Preparing the workforce through education, retraining and support systems will be essential in mitigating the risks while maximizing the potential benefits of AI's integration into the economy.

Technology has historically had a triple impact on occupations: transforming existing roles, replacing others entirely, and ultimately creating completely new jobs. Advancements in technology have introduced more sophisticated equipment and techniques that enhance efficiency, accuracy, safety and more. Automation, advanced manufacturing techniques and other industrial innovations have significantly increased productivity across Minnesota's economy. Businesses can now produce goods and services more efficiently, reducing costs and increasing output, which contributes to overall economic growth.

Technology has fostered a culture of innovation and entrepreneurship in Minnesota, particularly in sectors like "fintech", "biotech" and "medtech", where the state has long been a leader (for instance, the Mayo Clinic is the largest AI patent filer in its industry). The presence of major research institutions and a robust startup ecosystem has long attracted investment and talent, leading to the development of cutting-edge products and services. By embracing technology, Minnesota businesses have been able to compete more effectively in global markets.

However, this also illustrates the double-edged sword of technological advancement and automation – while new opportunities arise and existing roles evolve, some jobs may be changed or displaced. The challenge lies in managing these transitions effectively, ensuring that workers have the skills and support needed to adapt to changing economic landscapes. Lessons from history underscore the importance of proactive planning, investment in K-12 and higher education, and retraining to navigate the complex dynamics of technological change. This is why measuring exposure of occupations, industries and geographies within Minnesota is important.

While the everyday implementation of AI at work is relatively new, the idea is not. The concept of AI has been around for centuries and the term was first used in 1956, but it became mainstream with the introduction of ChatGPT in 2022. Now, thousands of researchers and businesses around the world are focused on harnessing the benefits of AI – and mitigating its risks – in all aspects of life.

One of those researchers is the founder and chairman of the Center for Curriculum Redesign, Charles Fadel, an internationally recognized expert on AI who was interviewed for this article. While focused more on education, his 2024 book, "Education for the Age of AI," cogently covers AI's impact on occupations in Chapter Two. Fadel summarizes that "AI will NOT replace most jobs any time soon. There is a significant misunderstanding of the difference between AI passing a test vs. doing a task vs. fulfilling a job. … One thing is sure, those [workers] with AI will beat those without…"

Fadel also points out that initial excitement about the potential of AI continues to build and that all industries are scrambling to ascertain the appropriate applications, which creates the potential for a bubble that may burst, as has happened historically in other sectors like railroads, radio and dot-coms. At this point the technology is still not widely leveraged, so if AI does not immediately live up to expectations, adoption of AI as a way to improve efficiency and outcomes may stall, at least in some industries and geographies. This could have a detrimental effect in the short-term, but progress will continue, and our state has an opportunity to take the lead in educating and preparing students, workers and businesses.

In discussions with AI experts like Fadel and through our literature review (view list at the end of this article), it is clear that AI has the potential to quickly and significantly influence various aspects of work. Still, our understanding of how AI could affect workers, occupations and industries is likely to evolve over time, with different insights emerging in the coming years. Whether AI will lead to job losses remains uncertain, as it could either replace or complement workers' roles, as well as create new work possibilities.

Due to this uncertainty, our study focuses on the extent to which jobs are exposed to AI, rather than predicting whether this exposure will result in job losses or gains. Forecasting the future applications of AI and large language models, or LLMs, is challenging, as new capabilities, shifts in human biases, and technological advancements could all impact the accuracy of predictions about how AI and LLMs will affect tasks and the development of AI-powered tools both in the short-term, and even more so in the long-term.

Even with all the research available, it was surprisingly difficult to find a report that provided a quantitative and well-reasoned measure of the impact on jobs. The best report we found was Occupational, Industry, and Geographic Exposure to Artificial Intelligence: A Novel Dataset and its Potential Uses by Edward Felten, Manav Raj and Robert Seamans. The value of their analysis is that it creates and validates a measure of an occupation's exposure to AI – it allows us to identify and count jobs that are exposed to AI.

The authors explain that "To construct our measure of occupational exposure to AI, we start by identifying different applications of these machine learning techniques and then link these applications to occupational abilities. Our methodology isolates the exposure to specific functions of AI and creates a measure of the aggregate exposure to AI at the occupation level by looking at the abilities used within an occupation. We consider 'labor' as the bundle of skills and abilities that are used within a specific occupation and this 'micro' approach allows us to examine how AI may be related to the abilities that each occupation requires. We link specific functions of AI to different types of abilities in the U.S. workforce using a crowdsourced dataset; then, considering the work content of each occupation, we aggregate the ability-level exposure to AI applications at the occupation level."

It is important to note that their measure of exposure "does not attempt to measure whether AI is a complement to or a substitute for labor, but rather how likely it is that the occupation is exposed to AI in some way." To provide context for the state of Minnesota, we were able to use their dataset to calculate occupational exposure via our Occupational Employment & Wage Statistics program.

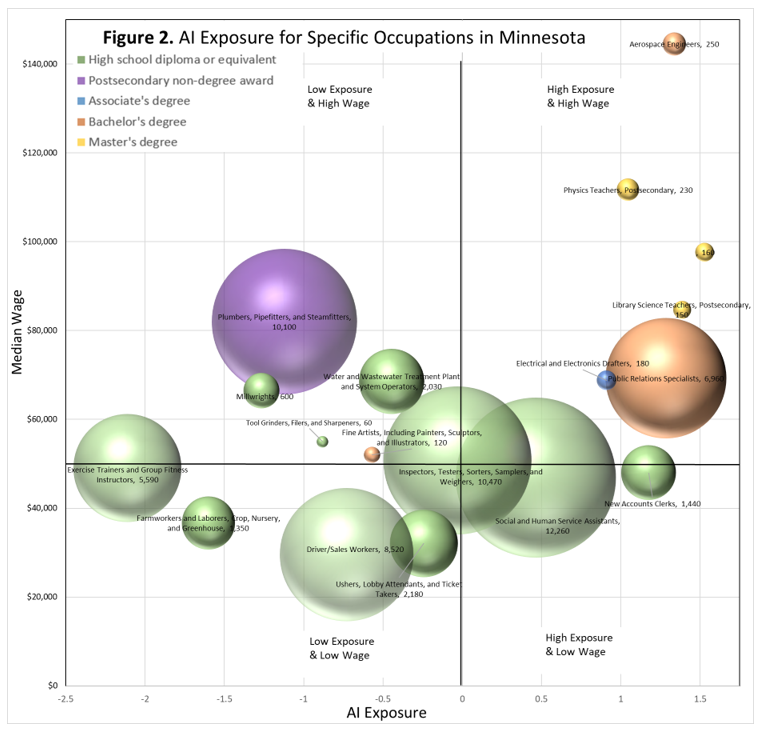

Figure 2 showcases a sample of 18 occupations across each quartile of AI exposure, illustrating the varying degrees to which different jobs are affected by AI. For example, Genetic Counselors had the highest exposure rating, while Exercise Trainers & Group Fitness Instructors had the lowest.

Genetic Counselors, a high pay occupation, can leverage AI for tasks like patient onboarding, initial consultations, and data analysis, particularly for less complex cases. AI can assist in organizing patient information and interpreting genetic data, making the process more efficient. This is an occupation where almost all required skills and abilities would benefit from AI.

On the other hand, Exercise Trainers & Group Fitness Instructors, a lower paid occupation, are less exposed to AI due to the hands-on nature of their work. These professionals require direct physical interaction with clients, must adjust in real-time based on feedback and provide motivation and encouragement on the spot. Much of the feedback during a session is based on qualitative observations and conversations, rather than analyzing large datasets or summarizing research. As of now, AI is not as well-suited to benefit workers in this occupation.

Across the board, AI has the potential to improve the efficiency of daily tasks in many jobs, but especially those that tend to have higher educational requirements and higher wages. Seventy percent of employment in the first quartile, representing occupations with the highest exposure to AI, have a median wage higher than $60,000 per year. Notably, 54 occupations in this high-exposure quartile boast median wages above $100,000 per year.

The type, degree, and frequency of jobs that AI can assist with will determine how different industries in Minnesota are exposed to AI. Industries with a high concentration of occupations most exposed to AI are directly affected by this exposure. Even with the limited sample of occupations shown in Figure 2, the connection between occupation and industry is clear. For example, Business Schools, Educational Support Services, Junior Colleges, Universities, and Elementary & Secondary Schools fall into the highest industry exposure quartile. Notably, three of the occupations in Figure 2 are educators, and nearly one in five occupations in the most exposed quartile are occupations in the Educational Services industry.

Education was not highlighted randomly—it deserves thoughtful consideration. The Educational Services industry is not only highly exposed to AI at all levels, but educators themselves will also be responsible for equipping students with the necessary skills to compete in the labor market.

Other industries that are more highly exposed to AI include Professional & Technical Services, Finance & Insurance, Information, Administrative Support Services, Management of Companies, Manufacturing, and Health Care & Social Assistance. As shown in Figure 4, the larger subsectors that will likely have higher concentrations of jobs that use AI include Accounting, Tax Preparation, Bookkeeping & Payroll Services, Legal Services, Insurance Agencies & Brokerages, Insurance Carriers, Computer Systems Design & Related Services, and Management, Scientific & Technical Consulting Services.

Some experts note that the present wave of AI technology advancement may be plateauing; however, even at this stage, it is still spurring enormous changes for various aspects of certain jobs. What comes next will be even more paradigm shifting not just for work, but for education and likely all aspects of life. When we spoke with him, Fadel said that "In the next 30-40 years, we will get to Artificial General Intelligence. We cannot predict the timing of the breakthroughs, but we can say that in the life of our students, it is going to happen; and our education system must help them prepare for the changes."

As shown in Figure 1 and Figure 3, occupations and industries with higher exposure tend to have higher educational requirements. In contrast, only 26% of employment in occupations that typically require a high school diploma or equivalent for entry are in the highest exposure quartile, while 75% of employment in occupations that typically require a bachelor's degree is found in the top quartile. Within the top 50 occupations with the most exposure to AI, only five have educational requirements below a bachelor's degree. Conversely, of the bottom 50 occupations with the least exposure to AI, only two typically require education beyond a high school diploma.

Driven by unique industrial mix, geographies will also have different exposure to AI. In general, metropolitan counties will have higher exposure than more rural counties, because they have a higher percentage of people employed in high-exposure occupations and industries. Hennepin County has the highest exposure rating in Minnesota while Todd County has the lowest.

All seven of the counties in the Twin Cities metro area rank in the top half, with Hennepin, Ramsey, Dakota, Washington, and Anoka all in the top 20. Other metro areas including Stearns County (St. Cloud), St. Louis and Carlton (Duluth), Clay (Fargo-Moorhead), and Nicollet (Mankato-North Mankato) are also in the top 30.

However, there are outliers where the unique local economy bucks the trend. Norman County, located on the rural western border of Minnesota is the second most exposed, and third highest is nearby Red Lake County. Both are dominated by agriculture and have a large number of farms, most of which do not have employment captured by the dataset used for this analysis due to self-employment. Instead, both counties have a substantial share of employment in the Health Care, Educational Services, and Public Administration sectors that have high AI exposure ratings.

Every business in every county has the opportunity to benefit from AI in some way, but levels of adoption will vary greatly based on industry, need and individual initiative. By embracing AI, businesses across the state may be able to benefit from innovations in information, human resources management, logistics, e-commerce and more. These technological advancements could also improve the quality of life for Minnesotans, with benefits such as better access to information, improved communication infrastructure and more efficient public services. These improvements will make Minnesota an attractive place to live and work, helping to retain talent and attract new residents to the state.

AI is transforming tasks for jobs across industries and geographies, raising both optimism and concern. While AI has the potential to increase efficiency, drive innovation, reduce tedious work and create new job opportunities, there is also significant worry about widespread job displacement and inequitable economic effects. That's why it is important to understand the exposure of Minnesota occupations and industries to AI to plan for strategic workforce development, economic planning and policy interventions and prepare for future impacts of AI on Minnesota jobs and our workforce.

Major employing industries in Minnesota such as Management of Companies, Manufacturing, Finance & Insurance and Health Care & Social Assistance are poised to benefit from AI, yet these same sectors are also at higher risk of disruption, especially in white-collar jobs that have traditionally been considered stable. The challenge lies in preparing workers through education, retraining and support systems to navigate this transition smoothly, ensuring that AI's benefits are broadly shared while mitigating the risks of economic disruption. The key to successfully navigating this shift will be ensuring that the Minnesota workforce is equipped with the skills needed to adapt to a labor market transformed by AI – and that Minnesota government, business and community leaders are prepared to position the state's economy to optimize the benefits of AI.

Helpful Background Research on AI: