by Mark Schultz

December 2021

As Minnesota employers look for ways to find new workers, they may want to also look at commuting patterns. Minnesota is a net importer of labor, meaning we attract more non-residents to fill jobs than there are residents who leave the state for work. In all, close to 114,000 non-resident workers enter the state to work compared to almost 100,500 Minnesota residents who commute to other states for work.

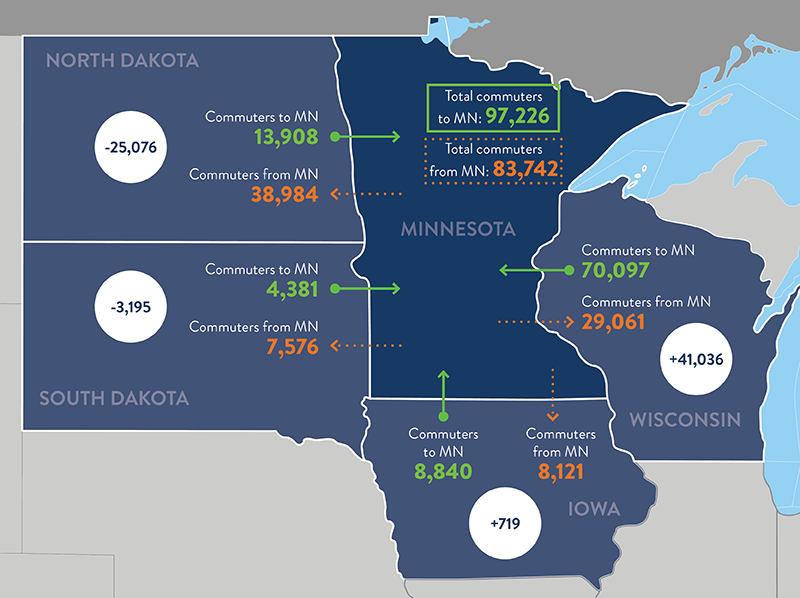

Minnesota draws 97,226 workers from the states bordering us and another 16,517 people from other states as far away as California. Meanwhile, 83,742 Minnesota residents cross the border to work in neighboring states and another 16,682 Minnesotans work in states outside the immediate 5-state region. While over 2,775,000 people both live and work in our state, with the ongoing tight labor market Minnesota employers might benefit from increasing the number of those who commute in from adjacent states and/or attempting to reduce the number of residents who commute out for their jobs (see Figure 1).

Source: U.S. Census OnTheMap

NOTE: Minnesota has workers coming in and residents going out to work in other states (i.e., IL, MI, MO, TX, CA, etc.) as well. The total inflow is 113,743, and the total outflow is 100,424. Figure 1 reflects only the surrounding states of IA, ND, SD, and WI.

According to data from the Census Bureau's On the Map tool, Minnesota draws workers from and sends workers to many different states, but looking just at the four surrounding states Census data shows positive inflow from two neighboring states and negative outflow to the other two. In sum, there are more non-resident workers who enter Minnesota from Wisconsin for work (70,097) than there are Minnesota residents who leave the state for jobs in Wisconsin (29,061). The same holds true for Iowa, where 8,840 people come in from Iowa while 8,121 people exit Minnesota to work across our southern border. On the other hand, Minnesota sees more residents leaving the state for work in both North and South Dakota than there are residents of those two states coming into Minnesota for their jobs (see Table 1).

Individual state-to-state flows provide additional insight on commuting patterns. For example, Minnesota draws the most workers from Wisconsin (70,097), likely because of the proximity of two of our major metro areas – the Twin Cities and Duluth – to the border with Wisconsin. The Twin Cities by itself draws in more than 45,000 workers from Wisconsin, where population – and jobs – are less densely concentrated. As a larger employment center, Duluth also draws in nearly 9,000 workers from Douglas and other counties in Northwest Wisconsin.

Conversely, Minnesota exports the most workers to North Dakota (38,984) due to our proximity to their major metro areas: Fargo and Grand Forks. These two thriving cities are the largest employment centers just across the border from Northwest Minnesota. In the fast-growing Fargo-Moorhead MSA, nearly 17,000 workers from Clay County and around 1,000 workers from both Becker and Otter Tail County were commuting to the Fargo, North Dakota side for work; whereas only about 6,000 workers from Cass County, North Dakota commuted into Minnesota to work on the Moorhead side.

Similarly, Sioux Falls, South Dakota is the largest employment center just across the border of Southwest Minnesota. More than 3,000 Minnesota residents drive into the thriving Sioux Falls area for work according to commuting patterns. Minnesota-Iowa job flows are somewhat equalized as both Southern Minnesota and Northern Iowa are relatively sparsely populated. Data show that larger metro areas offer more and different jobs that may not be available in less-populated, more rural areas, attracting commuters across state borders.

Table 1. Minnesota Commuter Flows with Neighboring States, 2019

| State | Commuters to Minnesota | Commuters from Minnesota | Net Commuters Into or Out of Minnesota |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wisconsin | 70,097 | 29,061 | +41,036 |

| North Dakota | 13,908 | 38,984 | -25,076 |

| Iowa | 8,840 | 8,121 | +719 |

| South Dakota | 4,381 | 7,576 | -3,195 |

| Source: U.S. Census OnTheMap | |||

Among Minnesota and its four neighboring states, Wisconsin is the only state that experiences a larger number of people commuting out for work, losing almost 52,000 more residents to jobs in other states than there are workers who come in. While the four remaining states see more outsiders travel into their respective states, there is significant variation in the difference between those who commute in and commute out.

By far the largest difference is seen in North Dakota, where 55,491 non-resident workers come into the state whereas only 18,797 residents leave for work, a difference of 36,694. Minnesota came in second place with 13,319 more people coming into the state than leaving for jobs. Both Iowa and South Dakota also bring in more non-resident workers than residents leaving the states with differences of 8,452 and 7,210 more people entering, respectively. Minnesota, however, has the largest number of residents who stay within state borders to work their jobs as well as the highest total number of workers in the state (those who commute in and those who both live and work in the state) (see Table 2).

Table 2. Inflow, Outflow, and Interior Flow by State (2019)

| State | Commute In | Commute Out | Commute Internally |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minnesota | 113,743 | 100,424 | 2,775,145 |

| Wisconsin | 109,669 | 161,667 | 2,770,272 |

| Iowa | 109,454 | 101,002 | 1,444,896 |

| South Dakota | 28,112 | 20,902 | 396,531 |

| North Dakota | 55,491 | 18,797 | 362,141 |

| Source: U.S. Census OnTheMap | |||

In the midst of a labor force shortage, where the state has far more available jobs than unemployed job seekers available to fill them, Minnesota employers may benefit from examining commuting patterns. Specifically, they could aim their recruiting at bringing in more workers from bordering states or attracting workers that currently leave the state for work, all while ramping up efforts to retain their current workforce. This may be an uphill battle given the current labor force landscape, and overarching population and employment concentration patterns, but efforts could pay off.