by Teri Fritsma, Minnesota Department of Health

December 2023

When it comes to the health care workforce, there are two stories: an urban story and a rural one. This is true both in Minnesota and in every other state in our country. As the labor market rebounds from the worst effects of COVID, shortages among Minnesota's health care workforce remain a significant challenge, even in our major metropolitan areas. But in our small town and isolated rural communities, which have long struggled to retain and attract health care workers, workforce shortages are not just a labor force issue. The presence or absence of even one dedicated clinician in a rural community can help determine whether the entire community flourishes or flounders; indeed, it can be the difference between life and death for patients who need care.

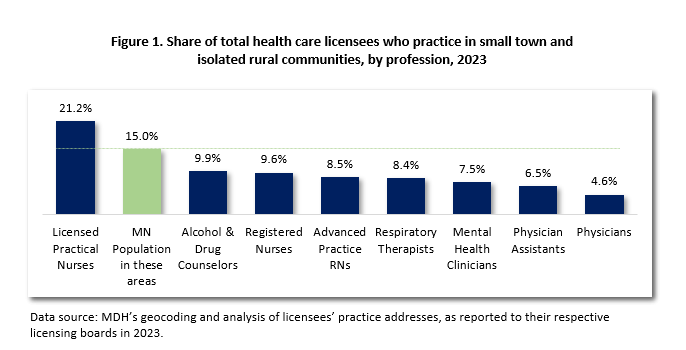

For this reason, it is critically important to understand what motivates the mere 7% of the entire licensed health care workforce to practice in small town and rural communities (compared to the approximately 15% of Minnesotans living in those areas). And what, if anything, stakeholders - e.g., policymakers, educational institutions, and rural communities themselves - can do to increase the share of clinicians who choose to live and work in rural areas? This article summarizes research findings that answer those questions.1

Although this health care workforce maldistribution is common to nearly every licensed health care occupation,2 this article focuses on three key professions: physicians, physician assistants (PAs), and advance practice registered nurses (APRNs). Of these professions, physicians are the most maldistributed, with only 4.6% of all physicians practicing in rural and small towns in Minnesota. And among PAs and APRNs, just 6.5% and 8.5%, respectively, live and work in rural areas of the state. PAs have a very broad scope of practice and are the "utility players" of health care, working in every specialty and every setting. They practice under the general supervision of a physician. APRNs (which include nurse practitioners, nurse midwives, and nurse anesthetists) also practice across many specialty types and settings, and in Minnesota their licenses allow them to practice entirely independently. Together, these three provider groups offer all types of general and specialty medical care from birth to death.

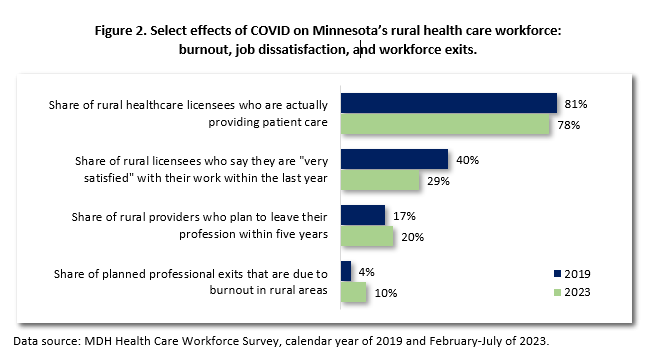

A note about COVID and the health care workforce. Based on several state data collection efforts3, we know that the COVID pandemic did lasting harm to Minnesota's health care workforce, the effects of which we could continue to feel for many years. Rural areas were not exempt.

This study relies on a dataset that merges records from two distinct sources: (1) administrative data from Minnesota's Nursing and Medical Practice licensing boards; and (2) data from the Minnesota Department of Health's 2021-2022 Health Care Workforce Survey of active health care providers.

The Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) receives a monthly transfer of administrative records from both the Board of Nursing and the Board of Medical Practice, the two licensing boards which govern the practice of nurses and physicians/physician assistants, respectively. As described below, this data is how we measure the key outcome we want to understand - where providers choose to practice (e.g., urban or rural). The study population includes all licensed physicians, physician assistants (PAs) and APRNs who had active Minnesota licenses as of July 25, 2022.

As mandated in Minnesota state statute, MDH surveys all physicians, PAs, and APRNS at the time of license renewal. Physicians and PAs must complete the survey before being able to pay the license renewal fee, whereas APRNs take the survey after payment, causing a slightly lower response rate for nurses. The data for this study was collected from October 18, 2021 through July 25, 2022. The survey response rates were 95%, 98%, and 60% for physicians, PAs, and APRNs respectively, and final sample sizes for each profession was 11,019 (physicians); 2,174 (APRNs); and 2,174 (PAs).

We merged the licensing data and the survey data using license number, a unique identifier across the two datasets.

The dependent variable in this study is whether or not the provider is practicing in a rural area, based on the practice address they report to their licensing board. We operationalized the level of rurality using the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) typology, which incorporates measures of population density, urbanization, and daily commuting patterns to categorize the level of rurality for regions at the level of US census tract.

Providers were coded as practicing in either an "urban" or "rural" community. The urban category includes large metropolitan centers (such as the Twin Cities, Rochester, Duluth, and others) as well as smaller micropolitan areas (such as Bemidji, Brainerd, and others). The rural category includes small towns such as Litchfield (with a population of approximately 6,650) Crosby (2,780) and Perham (3,500), as well as more remote communities that are a long distance from any urban center, such as Pine River (population 891), Isle (818), and Red Lake Falls (1,366).5

Using MDH survey results, we also measured the considerations that providers weighed when deciding on the type of area (rural versus urban) in which they live and work. The goal of the analysis was to identify the relative importance of each factor when controlling for all others. This allowed us to go beyond most previous research efforts that measure the zero-order effect of one consideration or policy intervention, to identify factors that have strong and/or consistent effects even when confounding, intercorrelated items are statistically controlled.

To measure this, we developed a set of 17 survey items that respondents were asked to rate on how important each one was to them as they considered the type of area in which to live and work (with response options including "very important"/"somewhat important"/"not important at all"/"did not apply to me"). We began by identifying a general list of items already identified in both the academic literature and policy as being related to the choice to practice in a rural area. That list included five general but overlapping categories: family considerations; practice considerations; financial and loan forgiveness incentives; education and training experiences; and characteristics of the area itself. We then drafted 17 survey questions to capture various dimensions of each of these five considerations.

Given the challenges involved in measuring these complex thought processes, we conducted 22 cognitive interviews with various provider types to identify inevitable validity problems with our draft questions. Those interviews guided us to revise questions where the intent behind the question(s) was not translating correctly to respondents, or where there was redundancy among our original questions. The list below shows the complete set of these measures in their final form. The items map on to five general categories: family considerations (survey items 2, 4, 6, and 13); considerations about the way the provider could practice in the area (items 3, 7, 10, 14, and 16); loan forgiveness and other financial considerations (items 8 and 11); education and training experiences (items 5 and 12); and characteristics of the area itself (items 1, 9, and 15).

"Think back to how you made the decision to live in your general area. How important were each of the following considerations?" ("Very important" | "Somewhat important" | "Not important at all" | "Did not apply to me")

It's well known that the strongest and most consistent predictor of where providers choose to live and practice is where they grew up: having grown up in a rural area makes a person far more likely to choose a rural area in which to live and practice. Therefore, the region in which a person grew up is the key control variable in our model. We measure the area where the provider grew up with the following survey question:

"Which of these best describes the area in which you grew up?" (If you grew up in more than one type of area, choose the one you most identify with.)

We also include age as a control variable since rural providers are older, on average, than urban providers, and age may be correlated with others of these factors.

Our findings are based on a binary logistic regression model that predicts the likelihood of practicing in a rural area as a function of these various independent and control variables discussed above.

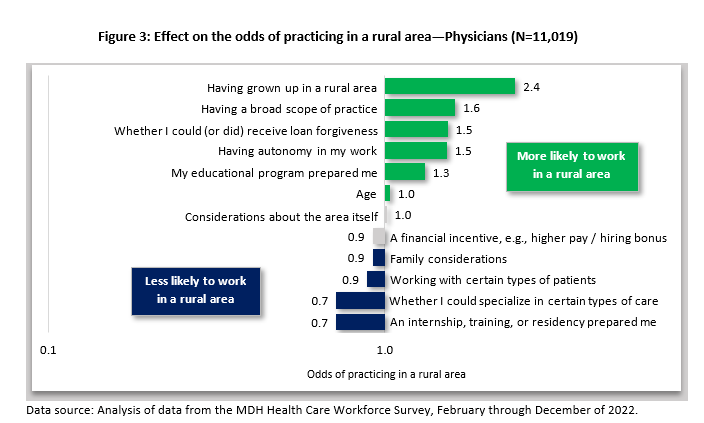

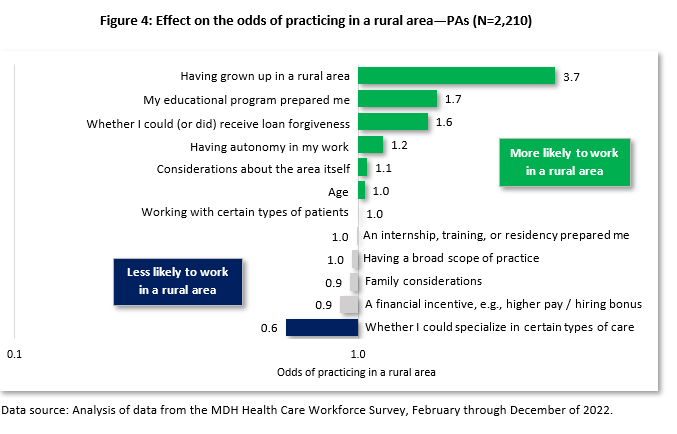

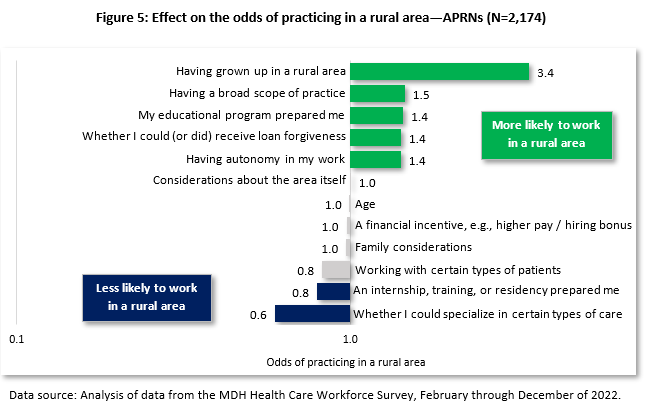

Figures 3, 4, and 5 show the results for physicians, PAs, and APRNs, respectively. The figures show the effect of each independent variable on the odds (or likelihood) of practicing in a rural area. Bars shown in green represent a significant positive effect on the likelihood of practicing in a rural area; bars shown in blue represent a significant negative effect on the likelihood of practicing in a rural area; and finally, bars shown in gray indicate that the item had no statistically significant effect.

Findings for physicians (see Figure 3) show that - after controlling for the outsized effect of having grown up in a rural area - the key factors that encourage physicians to practice in a rural area include four important items: (1) being able to have a broad scope of practice; (2) whether the provider could (or did) receive a loan forgiveness grant; (3) the ability to have autonomy in one's work; and (4) attending an educational program that offered preparation for caring for patients or clients "in an area like this (urban/rural)." These results are illuminating, and point to factors that policymakers and other stakeholders can actually exert some control over, namely loan forgiveness and educational experiences. Rural loan forgiveness grants, which are administered by the Minnesota Department of Health's Office of Rural Health and Primary Care, offer a set dollar amount for physicians, PAs, APRNs, and other health care professionals who commit to practicing in a rural area for at least three years. We can see from this finding that, regardless of where a physician grew up, having received (or having the ability to receive) a loan forgiveness grant is one of the strongest predictors of where they will decide to practice. Rural educational experiences, for example, the University of Minnesota's RPAP program, also have a significant impact on choosing rural practice. Together, these two findings indicate that there are levers we can use not just to retain - but also to redistribute - physicians from urban to rural areas.

Another interesting finding involves the nature of physicians' practice itself. Whereas urban practice often involves finer specialization, rural practice generally requires physicians to be generalists, because the lack of other local specialists leave gaps in care that rural providers must fill. Family medicine physicians who work in urban areas may not deliver babies, for example, but those working in rural areas may, since those areas often lack a board certified OBGYN specialist. The results here indicate that broad scope and greater autonomy in practice are meaningful and important considerations for physicians when they are deciding where to live and work.

Another interesting finding here is the relative lack of importance of other factors that are often assumed to be critical, including financial incentives, family considerations, and considerations about the area itself. Apparently, once holding other variables constant, these factors are minimally or not at all important in physicians' decision-making process. This would suggest that recruitment approaches emphasizing quality of life in rural areas are not particularly persuasive compared to other incentives. Recruiters might do better to focus on the broader scope of practice and "whole-person care" that are more typical in rural areas, as opposed to the availability of recreational activities, for example.

Not surprisingly, some factors actually have a negative effect on the likelihood of choosing to practice in a rural area (or, put another way, have a positive effect on choosing to practice in an urban area). The ability to work with certain types of patients or specialize in certain types of care is associated with choosing urban practice, which is not surprising since urban physicians are likely to be more specialized in their practice than their rural counterparts. Finally - and somewhat counterintuitively at first glance - having a residency, clinical training, or other internship that "exposed me to what it's like to work in this area, or a similar one" is associated with practicing in an urban area. This makes sense when we pause to consider that the vast majority of clinical training experiences for physicians occur in urban settings in Minnesota.

Figure 4 shows the results from an identical statistical model, this time for PAs. Here we see some similarities and some differences from physicians. Similar to physicians: for PAs, a loan forgiveness incentive, having attended an educational program that prepared them, and having autonomy in their work were all significant considerations prompting them to choose to practice in a rural area. Also similar to physicians, being able to specialize in certain types of care was a driver of urban, not rural, practice, and family considerations had no net effect. Unlike physicians, however, considerations about the area itself had a substantively small (though still statistically significant) influence on PAs who ultimately chose to work in a rural area, and perhaps most importantly, the possibility of having a broad scope of practice had no impact. Perhaps this difference reflects the fact that PAs have somewhat less control over how they practice than physicians do; PAs still practice under the general oversight of a physician, and this oversight can take different forms depending on the region and/or the organization. PAs may therefore perceive that their scope of practice is more determined by their supervising physician than by their region.

Finally, Figure 5 shows the results of the same model with the APRN sample. These findings are again generally quite similar to physicians, with a few slight differences. Again we see that family considerations and considerations about the area itself are not significant predictors of the decision to choose to practice in a rural area, whereas having a broad scope of practice, having autonomy at work, having attended an educational program that prepared one to work in a rural area, and having received (or being eligible for) a loan forgiveness award were all significant predictors of choosing to "practice rural" once having grown up in a rural area is controlled. These findings may look more similar to those of physicians since, again, in Minnesota, APRNs are licensed to practice independent of oversight from any other clinicians.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies that goes beyond looking at one or two factors in isolation to predict the likelihood of rural practice. Being able to control for the overwhelming impact of having grown up in a rural area helps us illuminate several key findings for this group of providers. First, contrary to what is often assumed, family considerations, and considerations about the area itself, have no impact on whether or not physicians or APRNs choose to work in a rural area (and area considerations have only a very modest impact on PAs' choices). Recruiters in rural areas often use the slower-paced lifestyle, safety, and proximity to recreation as an enticement, but perhaps these factors are not particularly germane to these clinicians' decision-making processes. Instead, our findings indicate that it might make more sense to focus on the nature of the work itself - the ability to really get to know one's patients and to practice broadly, with more autonomy than may be afforded in urban settings.

A second valuable finding to come from this research is that for all three professions, certain modifiable factors make a significant difference in influencing health care workforce to choose to practice in rural areas. Both loan forgiveness and rural educational experiences have a consistent positive impact on encouraging these three groups of clinicians to practice in rural areas. This suggests that (increased) public investment in both of these sorts of initiatives, and similar ones such as "grow your own" initiatives in rural clinical settings, would almost certainly yield desirable outcomes for rural communities.

Rural areas struggle to attract and retain health care providers, and the loss of retiring or burned-out physicians, PAs, and APRNs can devastate remote communities. This research takes a first step at modeling the factors that may tilt the scale toward a more robust rural health care workforce. Other fruitful areas of inquiry include examining whether these same findings hold among other types of providers (e.g., dental and mental health); looking more deeply at retention of health care workers in rural communities; and collecting more qualitative data on how and why these factors encourage providers to choose rural practice.

1These findings were originally published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Network Open. Original citation: "Factors Associated with Health Care Professionals' Choice to Practice in Rural Minnesota," by Teri Fritsma, Carrie Henning-Smith, Jacqueline Gauer, Faizel Khan, Mark E. Rosenberg, Kirby Clark, Elizabeth Sopdie, Angela Sechler, Michael A. Sundberg, and Andrew P.J. Olson.

2The one exception is licensed practical nurses (LPNs), 21.2% of whom practice in isolated rural or small town communities; see Figure 1.

3The findings in this section rely on four main data sources. (1) MDH's analysis of administrative data from health licensing boards; (2) the MDH Health Care Workforce Survey; (3) DEED's Occupational Employment Projections, and (4) the Minnesota Office of Higher Education's postsecondary data records.

4The number of nursing graduates comes from the Board of Nursing Education Report (2022). It should also be noted that the RN and APRN supply distinctions are oversimplified; in reality, some RNs have MS degrees and some APRNs have BS degrees. (And all APRNS are also RNs.)

5Within each profession, a minority of providers reported out-of-state practice addresses (11% for PAs; 19.2% for APRNs; and 23.3% for physicians). These addresses could not be geocoded, and therefore we had to exclude these providers from our analysis.