June 2018

PDF of article

Minnesota and the rest of the country are grappling with the beginnings of an unprecedented labor shortage.

The following writers contributed to this article: Steve Hine, Dave Senf, Sanjukta Chaudhuri, and Oriane Casale.

As has been our practice for the last six years, the State of the State issue of Trends each June provides an overview of the state’s labor market. Our previous State of the State issues emphasized our progress in recovering from the Great Recession.

But while we concentrated on which industrial sectors, regions and demographic groups were recovering the fastest or slowest, looming on the horizon was an unprecedented labor shortage. As you will read in this issue, that labor shortage has now arrived.

The tight labor market is uncharted territory when you consider the demographic trends impacting our workforce over the past 60 years. Baby boomers began entering the workforce in 1962 and continued doing so through 1980. It wasn’t until the turn of the century that the first of the boomers turned 55 and, in some cases, began thinking about early retirement. For the last 40 years, this bulge in our population has provided an abundance of available workers.

Simultaneously, the number and share of women in the workforce grew dramatically. Between 1960 and 2000, the labor force participation rate of women in the U.S. increased from 37.8 percent to 60 percent, a nearly 60 percent increase in the participation rate of half of our population.

But that all came to a screeching halt around 2000 as baby boomers began to hit their late 50s and female participation hit its upper limit. Here in Minnesota, we saw annual increases in our labor force drop from about 40,000 workers per year between 1976 (when we first started estimating state-level numbers) and 2000 to less than 15,000 per year since. This drop was masked, however, by the recessions of 2001 and 2008 and the lethargic expansion between them. The depth of the Great Recession also meant that we were well into the current recovery before worker shortages began to appear.

But now, with the current expansion officially the second-longest on record and the U.S. unemployment rate at its lowest level since 1969, we are facing conditions as tight as any of us can remember. Because the baby boomer generation will continue to turn 65 for the next decade, these conditions will remain with us for some time. Welcome to the uncharted territory of prolonged worker shortages.

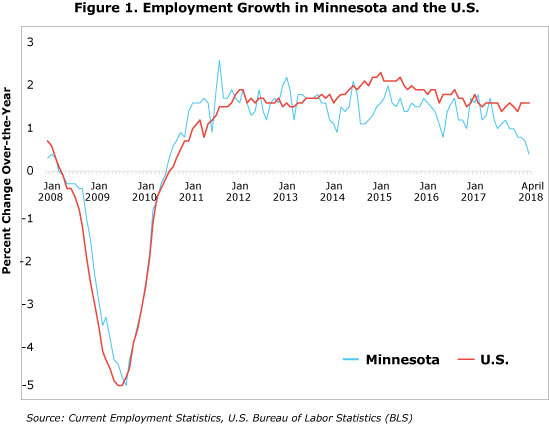

Minnesota employment grew 1.3 percent for the second straight year in 2017, but most of that growth occurred during the first half of the year. Job growth averaged 1.6 percent in the first six months last year before slipping during the second half to 1.1 percent. That trend has continued this year, with job growth averaging 0.7 percent through the first four months.

Minnesota job growth basically mirrored the national rate between 2011 and 2014 but has lagged the U.S. pace since 2015. Minnesota and U.S. job growth averaged 1.6 percent from 2011 to 2014. Between 2015 and 2017 job growth tailed off to a 1.4 percent average in Minnesota, while U.S. job growth accelerated slightly to a 1.8 percent average. U.S. job growth has remained fairly steady since, averaging 1.6 percent since April 2017, while Minnesota job growth downshifted even further, averaging 1 percent over the same period. A noticeable gap between Minnesota and U.S. job growth has developed over the last 12 months (see Figure 1).

Minnesota’s lagging job growth is most likely due to labor supply problems as opposed to any weakening of labor demand. State job vacancies (a proxy for labor demand) reached a record fourth quarter high last year, indicating that demand for workers remains solid. Declining unemployment numbers (a proxy for labor supply) combined with climbing job vacancies pushed the unemployed/job vacancy ratio to 0.8, its lowest-level in the 18-year history of DEED’s Job Vacancy Survey.

A similar measure published by the Conference Board reported that Minnesota’s April 2018 labor supply/labor demand rate was 0.73, the fourth-lowest rate behind only Hawaii, North Dakota and Colorado. The national rate of 1.37 supports the notion that Minnesota employers are having a much harder time filling job openings than employers in most other states.

Minnesota’s 3.2 percent unemployment rate compared with the U.S. rate of 3.9 percent in April is more evidence of the state’s tighter labor market. The same can be said for Minnesota’s U-6 unemployment rate, which was 6.1 percent in April compared with the U.S. rate of 7.8 percent. U-6 rates, which include part-time workers who want to work full time and discouraged workers, provide a broader gauge of the pool of workers potentially available to fill job openings. Minnesota’s pool of possible hires is significantly smaller than the U.S. pool based on the U-6 estimate.

The state’s low unemployment isn’t unique, ranking 13th-lowest in April. Nearby states with unemployment rates at 3.2 percent or lower have also experienced slow growth so far in 2018. Average over-the-year job growth in those states during the first four months of 2018 were 0.7 percent in Indiana, 0.7 percent in Iowa, 0.5 percent in Nebraska, negative 1.3 percent in North Dakota, and 0.9 percent in Wisconsin. The pool of unemployed workers willing to fill job vacancies in these states has been drying up quickly and limiting job growth, just as in Minnesota.

Minnesota’s lagging job growth has occurred across all sectors except government (see Table 1). Private sector employment is up only 0.2 percent over the year in Minnesota compared with the 1.8 percent gain nationwide. Public sector jobs increased 1.4 percent in Minnesota but were flat in the U.S. Payroll numbers increased in educational and health services (up 6,000) and manufacturing (up 4,700) over the last 12 months, but job cutbacks in leisure and hospitality (down 3,300), construction (down 1,600) and professional and business services (down 1,300) trimmed overall private sector employment growth. Most of the gain in government employment was education-related at both the state and local government levels.

| Table 1. Employment in Minnesota and the United States, Over-the-Year Change, April 2018 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | Minnesota Job Change | Minnesota Growth Rate | U.S. | Minnesota Share of U.S. Job Change |

| Total Nonfarm | 11,500 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 1.97 |

| Total Private | 5,300 | 0.2 | 1.8 | 1.98 |

| Mining and Logging | -100 | -1.6 | 8.9 | 0.86 |

| Construction | -1,600 | -1.4 | 3.8 | 1.58 |

| Manufacturing | 4,700 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.54 |

| Trade, Transportation and Utilities | 1,200 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1.94 |

| Information | -800 | -1.6 | -0.9 | 1.79 |

| Financial Activities | 900 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 2.11 |

| Professional and Business Services | -1,300 | -0.3 | 2.6 | 1.78 |

| Educational and Health Services | 6,000 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 2.28 |

| Leisure and Hospitality | -3,300 | -1.2 | 1.7 | 1.62 |

| Other Services | -400 | -0.3 | 1.7 | 1.98 |

| Government | 6,200 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 1.91 |

| OTY (Over-the-Year) Change is from April 2017 to April 2018 using unadjusted employment. | ||||

| Source: Current Employment Statistics, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) | ||||

While job growth has been slowing in Minnesota since mid-2017, April's initial numbers were particularly low and might be the result of the wintery weather in early April.

Since March 2015, 70 percent or more of Minnesota's working age population has participated in the labor force, whether employed or unemployed but looking for work. The labor force participation rate rose to 70.5 percent in April 2018. With over 3 million employed people in Minnesota in April 2018, the employment-to-population ratio was at 68.2 percent, up substantially from its trough of 65.9 percent in November 2009 during the recession.

As was mentioned earlier, the official unemployment rate uses a somewhat narrow definition of the unemployed: the share of the civilian population ages 16 and above who, at the time of the monthly survey, were not employed in the past week and who have looked for work sometime in the past four weeks. The broadest definition of unemployment includes discouraged workers who have given up looking for work because they think they cannot find it, and marginally attached who have looked for work in the past year but not the past month. Together these represent an additional 11,300 potential workers. Another important group is involuntary part timers, who are working fewer than 35 hours per week and want but cannot find a full-time job. These 80,500 workers could potentially add many hundreds of thousands of hours of work in Minnesota.

The official unemployment rate also does not reveal anything about unemployment spells. The longer one remains unemployed, the higher the associated monetary and nonmonetary costs. Long-term unemployment is defined as unemployment lasting more than 26 weeks. In Minnesota, the number of long-term unemployed people has been falling since late 2011. In April 2018, there were about 14,400 long-term unemployed people in Minnesota, or 14.9 percent of all unemployed. This number has dropped from peak levels of more than 70,000 workers, or 35 percent of the unemployed, during and shortly after the recession.

Breaking out the data by gender, women have a lower unemployment rate then men in Minnesota, at 2.6 percent compared with 3.6 percent in April 2018.

By race, black unemployment stood at 6.8 percent in April, a 1.3 percentage point decrease over the year in Minnesota. While this is among the lowest rates seen in records dating back to December 2001 in Minnesota, the black unemployment rate continues to be more than double the white unemployment rate. White unemployment stood at 2.7 percent, while Hispanic unemployment stood at 3.6 percent in April 2018.

This past year, Minnesota Economic Trends ran several stories on the gender wage gap in Minnesota. Among full-time workers in 2015, women earned 14.5 percent less than men at the median. In every industry in Minnesota women's median wage rates were lower than men's, with the gender wage ratio ranging from 95.5 percent in arts, entertainment and recreation to 64.2 percent in finance and insurance.

Health care and social assistance, Minnesota's largest sector, provides a good example of the gender wage gap. Despite being comprised of 75 percent women, women's median wage rate is 28.3 percent less than men's in the sector. While some of the difference can be explained by the number of hours worked, age, education, detailed industry and occupational distribution, some remains unexplained.

Even additional education does not close the gender earnings gap in Minnesota. Men without a high school diploma earn 15 percent more than women without a diploma, while men with a high school diploma earn 28 percent more than women with a diploma. The male-female earnings gap increases to 30 percent with an associate degree and 31 percent with a bachelor's degree. The gap then begins to narrow at the master's degree level, with men earning 17 percent more than women. Finally, at the doctorate level, men earn 18 percent more than women.

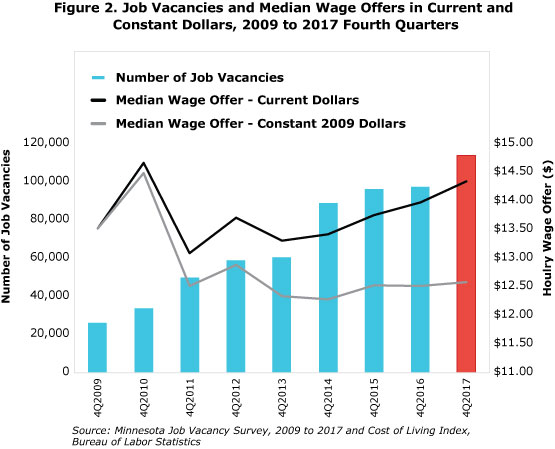

Job vacancies in Minnesota in 2017 exceeded all other estimates on record going back to 2001, with 122,929 job vacancies in the second quarter and 113,774 in the fourth quarter. With low unemployment, there were slightly more vacancies than unemployed people in Minnesota throughout 2017. The number of unemployed per vacancy was 0.9 during second quarter and 0.8 during fourth quarter.

The rising vacancy rate was further evidence of a tightening labor market last year. Vacancies were equal to 4.5 and 4.2 percent of all jobs in the second and fourth quarters, respectively. In such a tight labor market, it is no wonder that many employers are struggling to fill open positions and keep turnover in check.

Despite the tight labor market, wage offers have been rising slowly, barely keeping pace with inflation. Figure 2 shows vacancies and wage offers since the trough in vacancies at the end of the recession. While vacancies built back up to the highest level on record, wage offers dropped and then remained flat in constant dollars. So while current dollar wage offers show some growth, inflation has eaten away almost all of its value.

In fourth quarter 2017, the most openings by industry were in health care and social assistance with 23 percent, followed by retail trade (17 percent), accommodation and food service (14 percent) and manufacturing (9 percent). These are all large sectors with many jobs. The vacancy rate, on the other hand, allows us to determine which occupations have the highest share of vacancies to filled jobs. Accommodation and food service had the highest vacancy rate at 7 percent, followed by waste and administrative services at 6.8 percent and retail trade at 6.6 percent.

All of these sectors had median wage offers below the overall median of $14.34 per hour during fourth quarter 2017, with only two exceptions – manufacturing at $16.88 and administrative and waste management services at $14.82. In other words, the lower-wage sectors are showing the tightest labor market conditions and may be experiencing more difficulty hiring and retaining staff than higher-paid sectors.

Looking at specific occupations can shed more light on labor shortage conditions. Of the over 570 occupations with measured vacancies in fourth quarter 2017, the top seven accounted for 25 percent of all vacancies (see Table 2). All of these have median wages at or below $14 per hour, below the $14.34 for all vacancies.

In recent years, most of the occupations listed in Table 2 have grown in terms of the number of vacancies. Some, like retail salesperson, personal care aides and cooks, have grown substantially. Wage offers have also grown (up 5.9 percent across the board) but not necessarily in line with increasing demand. For example, median wage offers bumped up 19 percent for retail salespersons and 8.5 percent for cooks. But offers grew only 0.5 percent (or 0.6 cents) for personal care aides over this period.

| Table 2. Largest 10 Occupations in Fourth Quarter 2017 and Three Year Change* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupation | Vacancies | Vacancy Rate (%) | Median Wage Offer ($) | Percent Change in Vacancies | Percent Change Median Wage Offer |

| Total, All Occupations | 113,774 | 4.2 | 14.34 | 18.4 | 5.9 |

| Retail Salespersons | 8,278 | 9.8 | 11.97 | 38.5 | 19.1 |

| Personal Care Aides | 6,640 | 9.8 | 11.55 | 180.5 | 0.5 |

| Combined Food Prep and Serving Workers | 3,251 | 4.9 | 10.53 | 8.8 | 10.6 |

| Nursing Assistants | 2,918 | 9.4 | 14.00 | 15.7 | 16.7 |

| First-Line Supervisors of Food Prep and Serving | 2,649 | 17.6 | 13.40 | 19.4 | 7.5 |

| Cashiers | 2,592 | 4.1 | 10.71 | -25.2 | 8.0 |

| Cooks, Restaurant | 2,562 | 10.0 | 11.82 | 36.3 | 8.5 |

| Registered Nurses | 2,480 | 4.0 | 30.23 | -1.0 | 6.1 |

| Heavy and Tractor-Trailer Truck Drivers | 2,376 | 6.9 | 18.05 | 9.2 | 10.1 |

| First-Line Supervisors of Retail Sales Workers | 2,125 | 9.8 | 15.43 | -10.9 | 17.1 |

| *Change is measured between fourth quarter 2015 and fourth quarter 2017. | |||||

| Source: Minnesota Job Vacancy Survey | |||||

The good news here is that employers who can, are responding to the tight labor market by raising wage offers, even in low-skill, low-wage occupations. The bad news is that not all employers are in a position to increase wages. For example, only U.S. and Minnesota legislative entities have the power to substantially raise wages and wage offers for personal care aides. As personal care aide wage offers continue to fall behind wage offers in other occupations, the result is critical labor shortages for people and families who rely on these services.

Job growth is off to its slowest start in eight years in Minnesota. Between 2011 and 2017, job growth averaged 1.7 percent, but it slipped to 0.7 percent this year as of April. As discussed earlier, the tightening state labor market – rather than waning labor demand – is probably restraining job growth as Minnesota employers find it increasingly difficult to fill openings.

Looking out one year, the jobless rate is likely to fall below 3 percent for the first time since 1999 during the year as job growth is expected to remain steady, albeit at the slowest rate since the state's job market began to rebound from the Great Recession in late 2010. Job growth is expected to average 0.9 percent for 2018.

The predicted 25,000 new jobs in 2018 will be spread across all but four industries (see Table 3). Small job losses are expected in natural resources and mining, information, utilities and federal government. Job growth in 2018 will be slower in most industries compared with the average annual rate achieved between 2011 and 2017. A few industries, however, will see faster job growth in 2018 than the average annual rate recorded over the last seven years.

Private educational services employment is an example of an industry that will see faster growth this year of 2.1 percent. Private educational services employment growth was reduced between 2012 and 2017 as private colleges and professional schools cut their workforces in response to falling enrollment. Enrollment soared during the recession but slumped as the economy improved over the last six years. Private colleges and professional schools employment is still expected to decline in 2018, but reductions will be much smaller than in recent years.

Thirteen industries are anticipated to add jobs as fast as or faster than overall job growth. Social assistance employment will grow the fastest, expanding by 3 percent, but still slower than in recent years. The next four fastest-growing industries will be construction; arts, entertainment and recreation; private educational services; and ambulatory health care services. Job growth in all these industries, except for private educational services, will be slower this year compared with average growth during the previous seven years.

Construction jobs, which have increased by 5.2 percent on average since 2011, will climb only 2.5 percent this year as construction companies struggle to ramp up their hiring in the tightening job market. Food services and drinking places is another industry that is expected to experience slower growth in 2018 compared with previous years. Jobs in food services and drinking places climbed 1.8 percent annually between 2011 and 2018 but are predicted to grow by just 0.6 percent over the next 12 months.

| Table 3. Minnesota Industry Forecast to 2019 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industries | 2011 | 2018 | 2019 | Average Percent Change 2011 - 2018 | Percent Change 2018 - 2019 |

| Total All Industries | 2,610,484 | 2,895,979 | 2,921,070 | 1.5 | 0.9 |

| Goods Producing | 372,576 | 426,636 | 429,866 | 2.0 | 0.8 |

| Natural Resources and Mining | 6,085 | 6,153 | 6,097 | 0.2 | -0.9 |

| Construction | 73,805 | 104,962 | 107,534 | 5.2 | 2.5 |

| Manufacturing | 292,686 | 315,521 | 316,235 | 1.1 | 0.2 |

| Service Providing | 2,237,908 | 2,469,343 | 2,491,204 | 1.4 | 0.9 |

| Utilities | 12,752 | 12,248 | 12,200 | -0.6 | -0.4 |

| Wholesale Trade | 122,409 | 132,727 | 134,511 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| Retail Trade | 270,003 | 294,586 | 295,942 | 1.3 | 0.5 |

| Transportation and Warehousing | 77,463 | 94,380 | 95,489 | 2.9 | 1.2 |

| Information | 53,361 | 49,593 | 49,275 | -1.0 | -0.6 |

| Finance and Insurance | 129,634 | 143,540 | 144,249 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

| Real Estate and Rental and Leasing | 32,417 | 33,837 | 34,028 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Prof, Science and Technical Services | 131,310 | 159,068 | 160,609 | 2.8 | 1.0 |

| Management of Companies | 72,625 | 78,789 | 79,359 | 1.2 | 0.7 |

| Administrative and Support and Waste | 119,218 | 128,498 | 129,590 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| Private Educational Services | 64,650 | 69,468 | 70,897 | 1.0 | 2.1 |

| Ambulatory Health Care Services | 126,325 | 153,532 | 156,220 | 2.8 | 1.8 |

| Hospitals | 98,716 | 111,948 | 113,000 | 1.8 | 0.9 |

| Nursing and Residential Care Facilities | 100,610 | 107,209 | 107,200 | 0.9 | 0.0 |

| Social Assistance | 73,057 | 95,558 | 98,442 | 3.9 | 3.0 |

| Arts, Entertainment and Recreation | 32,385 | 41,513 | 42,501 | 3.6 | 2.4 |

| Accommodation, including Hotels, Motels | 23,630 | 25,658 | 25,929 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Food Services and Drinking Places | 165,649 | 187,940 | 189,147 | 1.8 | 0.6 |

| Other Services | 113,091 | 114,717 | 115,160 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Government | 418,603 | 434,534 | 437,456 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| Federal Government | 32,529 | 31,990 | 31,945 | -0.2 | -0.1 |

| State Gov, Excl. Education | 37,155 | 39,410 | 39,590 | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| State Gov Higher Education | 64,953 | 65,563 | 66,041 | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| Local Gov, Excl. Education | 141,356 | 144,405 | 145,880 | 0.3 | 1.0 |

| Local Gov Education | 142,610 | 153,166 | 154,000 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| All employment data is unadjusted Current Employment Statistics (nonfarm wage and salary employment) jobs for the first quarter of each year.

Source: Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development |

|||||

Table 4 compares job growth by specific occupations. Job growth is predicted to be positive across all 22 major occupational groups, with 15 of the groups adding positions as fast as or faster than overall job growth. Construction and extraction, and personal care and service occupations are expected to grow the fastest. The slowest-growing occupations will be production; farming, fishing and forestry; and office and administrative jobs.

Job growth this year is predicted to be higher than over the previous seven years in seven occupational groups, including life, physical and social science occupations and community and social service occupations. Most occupational groups, however, will see slower growth in 2018 compared with the last seven years. Positions in personal care and management will grow the slowest this year compared with past rates.

| Table 4. Minnesota Occupation Forecast to 2019 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupational Group | 2011 | 2018 | 2019 | Average Percent Change 2011 - 2018 | Percent Change 2018 - 2019 |

| Total | 2,610,484 | 2,895,979 | 2,921,070 | 1.5 | 0.9 |

| Management | 135,049 | 173,452 | 175,264 | 3.6 | 1.0 |

| Business and Financial Operations | 152,854 | 173,080 | 174,647 | 1.8 | 0.9 |

| Computer and Mathematical | 83,759 | 97,942 | 98,408 | 2.3 | 0.5 |

| Architecture and Engineering | 45,576 | 54,882 | 55,491 | 2.7 | 1.1 |

| Life, Physical and Social Science | 29,137 | 25,886 | 26,152 | -1.7 | 1.0 |

| Community and Social Service | 69,778 | 64,233 | 65,045 | -1.2 | 1.3 |

| Legal | 17,545 | 19,643 | 19,863 | 1.6 | 1.1 |

| Education, Training and Library | 196,999 | 209,483 | 211,415 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Arts, Design, Entertainment, Sports and Media | 36,914 | 38,157 | 38,478 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| Healthcare Practitioners and Technical | 156,592 | 177,206 | 179,167 | 1.8 | 1.1 |

| Healthcare Support | 98,305 | 86,208 | 87,050 | -1.9 | 1.0 |

| Protective Service | 45,718 | 50,697 | 51,249 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| Food Preparation and Serving Related | 205,418 | 232,244 | 233,976 | 1.8 | 0.7 |

| Building and Grounds Cleaning and Maintenance | 77,243 | 79,792 | 80,909 | 0.5 | 1.4 |

| Personal Care and Service | 91,078 | 136,263 | 139,084 | 5.9 | 2.1 |

| Sales and Related | 250,624 | 272,257 | 273,823 | 1.2 | 0.6 |

| Office and Administrative Support | 409,786 | 416,792 | 418,534 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Farming, Fishing and Forestry | 4,183 | 2,832 | 2,843 | -5.4 | 0.4 |

| Construction and Extraction | 66,751 | 92,043 | 94,010 | 4.7 | 2.1 |

| Installation, Maintenance and Repair | 85,032 | 95,820 | 96,703 | 1.7 | 0.9 |

| Production | 200,566 | 217,453 | 217,580 | 1.2 | 0.1 |

| Transportation and Material Moving | 151,578 | 179,614 | 181,379 | 2.5 | 1.0 |

| Source: Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development | |||||