by Dave Senf

September 2021

For decades, we knew that a retirement wave was coming based on demographic shifts as baby boomers age. But the behavioral changes due to the pandemic leading to accelerated retirements weren't predictable even two years ago. Both the demographic and accelerated retirement trends are being seen around the country. This article takes a summary look at how decisions to retire early due to concerns over COVID-19, changes in life priorities, or healthier-than-expected retirement funds will impact Minnesota's labor force.

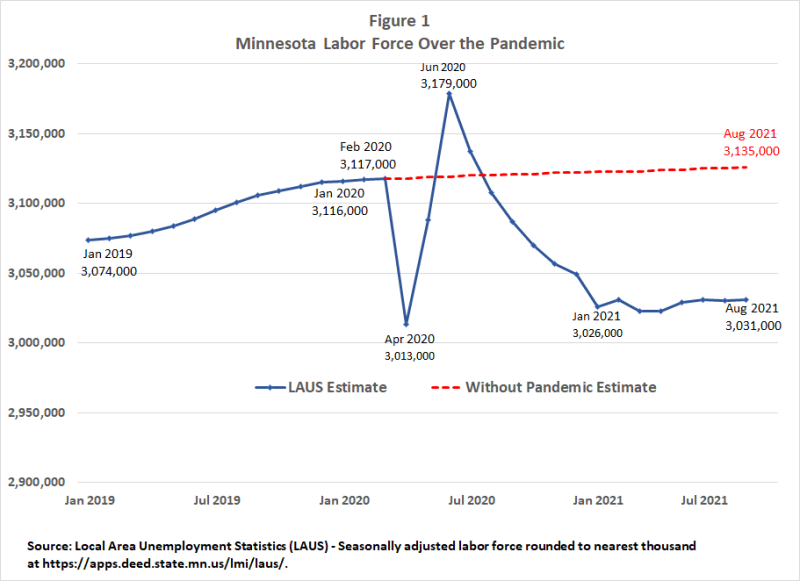

As the uneven economic recovery from the pandemic continues, employers in service sectors across the state – and around the country – are having their toughest time in the past two decades in finding and hiring enough workers to fill their record-high number of job openings. A large share of the hiring difficulties can be explained by the decline in labor force participation nationally and in Minnesota during the first year of the pandemic. According to seasonally adjusted Local Area Unemployment Statistic (LAUS) estimates, in August 2021 the state's labor force was down 2.8%, or 86,000 workers from February 2020 (Figure 1). The U.S. labor force is down 1.8% or 2.9 million workers over the same period.

Minnesota's current labor force shortfall may be even larger than the 86,000 worker drop off seen in the LAUS estimates, when considering projected labor force growth rates. The Minnesota State Demographic Center projected labor force growth of 5,500 per year between 2020 and 2025 before the pandemic. At that rate Minnesota's labor force would have grown to roughly 3,135,000 workers by August 2021 (shown in red in Figure 1), but we're 95,000 short of that number now. To put this in perspective, Minnesota's average annual labor force growth between 2015 and 2020 was roughly 20,000, so the 5,500 annual growth rate projection was already a steep drop from annual labor force increases of the past.

The 5,500 annual projected average for 2020-25 versus the 20,000 actual annual growth during 2015-20 period highlights the effect that retirement among the baby boom generation will and is having on the state's labor force growth over the next ten years. The flatness of the red-color labor force line in Figure 1 underscores that Minnesota, just like many states, will be dealing with minimal labor force growth in this decade as the working age population barely inches up. Ongoing tight labor markets and hiring problems will continue even after the pandemic-induced labor force drop off recedes.1

A variety of explanations have been advanced as to what is behind the pandemic-induced labor force decline and its slow rebound despite elevated job vacancy levels. Unemployed or underemployed Minnesotans surveyed have cited concern about being exposed to COVID-19 at work, child-care accessibility problems and the need to stay home because of online school instruction, or increased need to care for an older or disabled family member. Employers have frequently cited the disincentive effect of the federal enhanced Unemployment Insurance (UI) benefits, which ended earlier this month, as well as a mismatch between unemployed workers and open positions. Another factor that may be at play is an acceleration in retirement, in other words people retiring earlier than would have been previously expected.

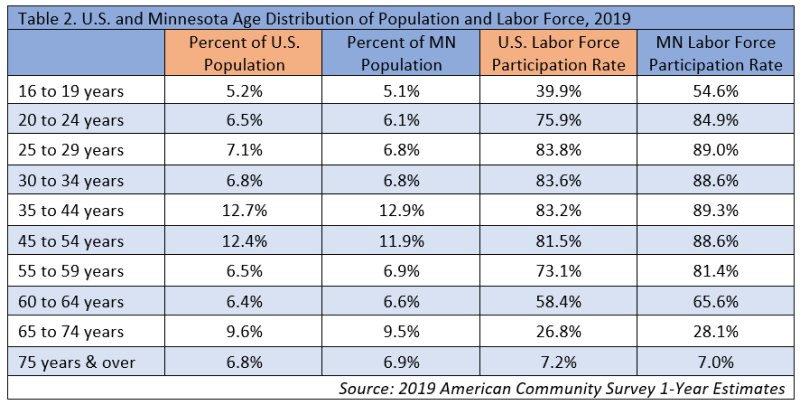

First, it is important to understand that Minnesota has long enjoyed one of the highest labor market participation rates in the country, and the state's rate is still well above the national average. This has been particularly true among women and older adults. Even now, as of August 2021, Minnesota's labor force participation rate is at 67.8% and compared to the national rate of 61.7%.

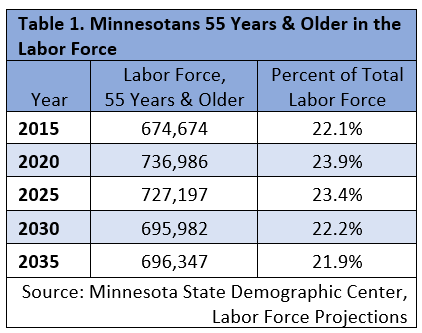

An uptick in U.S. workers retiring during the 2020 – 2030 period has been ominously discussed over at least the previous two decades because this is the decade when baby boomers are aging out of the workforce, having reached traditional retirement years (starting at 55 years for some industries). The youngest of the boomers are turning 57 this year while the oldest are celebrating their 75th birthdays. In Minnesota, as in many other parts of the country, the share of the state's population and labor force accounted for by 55-years-and-older individuals will reach record highs over the next few years (see Table 1). The 23.9% of the state's labor force accounted for by 55 years and older workers in 2020 is projected to be the highest share in any milestone year, but the share will be elevated through 2030, guaranteeing that the state's retirement rate and annual number of retirees will exceed rates and levels recorded in past decades.

An uptick in U.S. workers retiring during the 2020 – 2030 period has been ominously discussed over at least the previous two decades because this is the decade when baby boomers are aging out of the workforce, having reached traditional retirement years (starting at 55 years for some industries). The youngest of the boomers are turning 57 this year while the oldest are celebrating their 75th birthdays. In Minnesota, as in many other parts of the country, the share of the state's population and labor force accounted for by 55-years-and-older individuals will reach record highs over the next few years (see Table 1). The 23.9% of the state's labor force accounted for by 55 years and older workers in 2020 is projected to be the highest share in any milestone year, but the share will be elevated through 2030, guaranteeing that the state's retirement rate and annual number of retirees will exceed rates and levels recorded in past decades.

Many analysts have suggested that over the last two years national retirement numbers have significantly exceeded the pre-pandemic projections that just accounted for baby boomers aging into retirement years, and national data shows that labor force participation has decreased more among workers 55 and older during the pandemic compared to prime age (25 through 54-year-old) workers. While prime age participation has begun to rebound, older worker participation has remained far below pre-pandemic levels. These elevated retirement levels nationally during the last two years are attributed to COVID-19 and explain at least part of the decline in the U.S. labor force during the pandemic.

One potential sign of the impact of accelerated retirement during the pandemic: the percent of those age 55 and older that were out of the labor force because they were retired increased from 47.8% in the second quarter of 2019 to 49.9% in the second quarter of 2021 nationwide. The two-percentage points increase resulted in a significantly higher number than what had been expected even after considering the expanding number of 55 and older workers. Retirement numbers totaled roughly two million more than was projected and represent a significant share of the 2.9 million worker decline in the U.S. labor force between February 2020 and August 2021.

At the national level there is enough detailed and up-to-date data to divide the overall retirement rate for those age 55 and older into two parts; a demographic part related to shifts in the distribution of age, sex, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment, and a behavior part due solely to changes in retirement rates within the various demographic groups. For example, the retirement rate for 65-year-old workers is higher than 63-year-old workers. So, an increase in the population of 65-year-old workers would increase retirement numbers even if retirement rates stayed the same (demographic increase). More retirements would occur if the retirement rate for 65-year-old workers increased for whatever reason (behavioral increase).

Analysis of U.S. labor force data since 2006 shows that the retirement rate decreased from 2006 to 2012 and then rose eight out of the last nine years with large annual increases in 2020 and the first half of 2021. The retirement rate inched up 0.3 percentage points in 2019 due solely to demographic change. In 2020 the retirement rated jump 1.2 percentage points with 42% of the increase attributed to demographic change and 58% due to behavioral change. The rate continued to increase in 2021, by 0.9 percentage points, with 56% owing to demographic change and 44% to behavior change.

The expanded role of behavioral changes in the acceleration of retirement rates in 2020 and 2021 may be the result of some older workers retiring earlier than they originally planned because of the pandemic. The recent run up in assets, such as stocks and home values, may have made the retirement decision for higher income older workers a lot easier during the pandemic. For lower income older workers, layoffs and fear of exposure to COVID-19 at work may have forced many into retirement earlier than they planned risking long-term financial insecurity because of lower-than-anticipated savings and diminished payouts from pensions, Social Security, and other sources.2

Minnesota's labor force age distribution in 2019 was skewed slightly older than the U.S. labor force as 23.6% of Minnesota's labor force was 55 years or older compared to 22.7% nationwide. Minnesota has a slightly older distribution when it comes to population but the higher rates of labor force participation by the state's older workers is the main reason why Minnesota's labor force is slightly older (see Table 2). The slightly older labor force means Minnesota will see a higher percent of its workforce retiring over the next decade than nationwide and perhaps make the state more susceptible to increased retirement rates brought on by pandemic induced behavioral changes.

Unfortunately, up-to-date detailed data required to do a detailed analysis on recent retirement shifts in Minnesota, similar to the U.S. analysis provided by the Atlanta Federal Reserve Bank, is unavailable. However, by applying the 2nd quarter 2019 to 2nd quarter 2021 changes in U.S. 55 years and older aggregated labor force participation rates to Minnesota's U.S. 55 years and older aggregated labor force rates, it is estimated that Minnesota retirements increased by between 29,000 to 59,000 due to behavioral change above previously expected retirements from demographic change over the last two years.

The 29,000 to 59,000 range is based on Minnesota's behavioral change in labor force participation ranging from half of the U.S. change to the same as the U.S. change. Even if the lower 29,000 estimate is correct, the number of older Minnesotans who retired earlier than planned due primarily to the pandemic accounts for a substantial percentage of Minnesota's pandemic-induced labor force shortfall of 95,000 workers versus projections for August 2021.

While a pandemic-induced speedup in retirement may account for a sizable share of the labor force decline over the last two years, the long-term consequences are probably zero since the older workers who retired earlier than anticipated would have eventually retired a couple of years later and have been included in long-term labor force projections. As Minnesota's baby boomers continue to age, the state's retirement rate and numbers will continue to increase over the next few years before gradually receding. This will continue to slow the state's labor force growth throughout this decade if all other factors, such as net domestic and international immigration to the state, remain constant.

Pandemic-induced behavioral change may not persist as the pandemic fades away and the financial position of older Minnesotan's may change with the impact of financial winds on retirement savings. This may shift retirement decisions in the opposite direction leading to Minnesota retirement rates still increasing due to demographic change but not also due to behavioral change, which may have been a major influence over the last two years.

In conclusion, Minnesota, much like the rest of the nation, is facing a worker shortage not only due to long-term demographics changes but also to short-term behavioral changes, including accelerated retirements by those who would have been expected to work longer but are retiring early due to the effects of the pandemic.

1See the 2013 Minnesota State Demographer Center's report "In the Shadow of the Boomers" Minnesota's labor force outlook" on pending labor shortages.

2For more on research showing that U.S. retirement rates may have spiked over the last two years due to pandemic induced jump in retirement rates see the Atlanta Federal Reserve Banks, "Do Rising Retirements during COVID Reflect Demographic Trends?".