Luke Greiner

November 2021

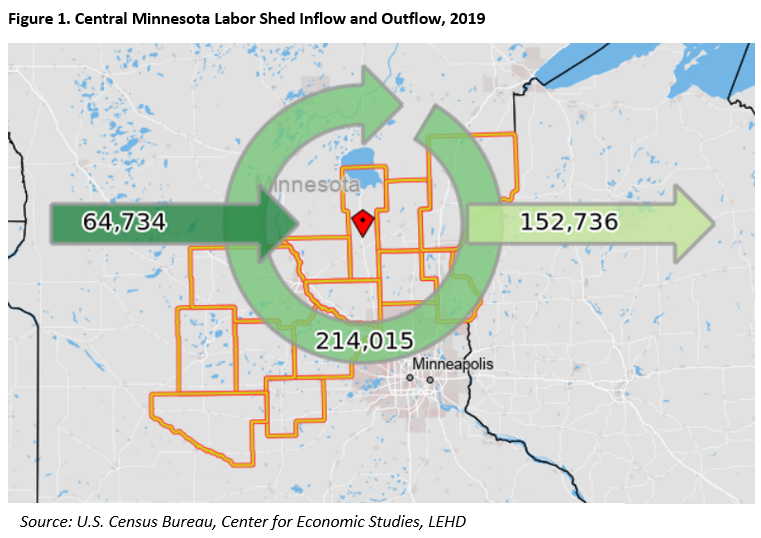

More than 150,000 Central Minnesota workers leave the 13-county area for work, some travel just across a county border while others commute rather long distances. This group of workers who leave represent about 42% of all workers living in Central Minnesota. Employment mobility can be a terrific benefit for workers and employers as a way to live in a desirable location while being employed in an occupation that might not be available locally or to gain access to higher paying labor markets such as the Twin Cities.

However, commuting long distances comes at a cost, and the data suggest that significant numbers of workers are spending time and money to achieve a nominal net gain, or worse, a possible net loss. Just over 40% of Central Minnesota workers who commute out of the region earn less than $40,000 per year. About 35% of those who work in the region are employed in the Twin Cities Metro area (Figure 1).

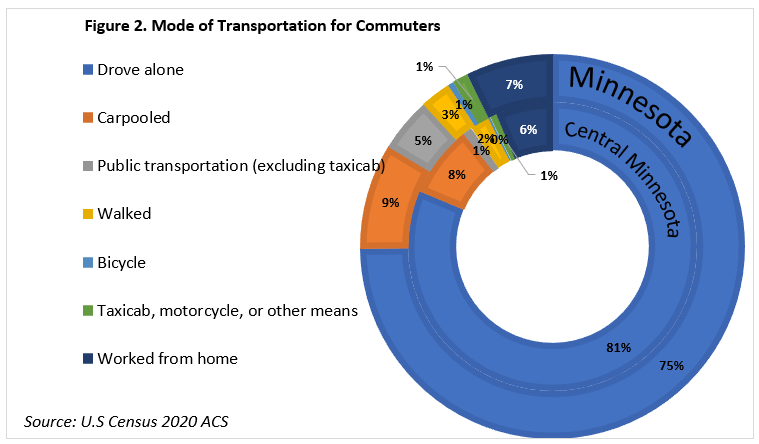

According to the 2020 five-year average, the vast majority of workers in the region drive alone to work (81%) and another 8% carpool. The remaining workers mostly worked from home (6%) while 4% either walked, rode bicycles, or took a taxi, motorcycle, or some other means (Figure 2). Keep in mind that the most recent five-year average data include just a single year of pandemic related workplace shifts. Carpooling substantially cuts the transportation costs of commuting, but few are willing or able to do it. Carpooling, while not always effective, can be incredibly efficient, cutting the cost and potentially decreasing traffic volumes on trunk highways.

The share of labor working from home to some extent is certainly higher now than is indicated in Figure 2. In fact, most recent national data from the Current Population Survey indicated that 10% of all workers were teleworking to some extent because of the pandemic in March 2022. Other national sources peg the overall rate of telework much higher, including Gallup that estimates 45% of full-time workers were working partly or fully from home as of September 2021, down from 69% in May of 2020. Their report also signals that remote work trends have been holding steady and trending permanent. The Gallup Survey reveals that “91% of workers in the U.S. working at least some of their hours remotely are hoping their ability to work at home persists after the pandemic”.

According to the Gallup study the key reason why so many workers are hoping to continue remote working is time preservation. More specifically, not having to commute, needing flexibility to balance work and personal obligations, and improved wellbeing (which likely results from having more time) are the top-cited reasons for preferring remote work.

The benefits of better work/home life balance and flexibility might have the added perk of helping women workers pursue abandoned professional aspirations or prevent some from leaving the labor force entirely. Since family caretaking is typically provided by women and commonly comes at the expense of professional development, many women are forced to choose between work or family. But with the rise of work from home flexibility it’s possible that after quarantines and school or daycare disruptions are less frequent, women workers may be able to capitalize on skills that they have been unable or unwilling to leverage in the labor market.

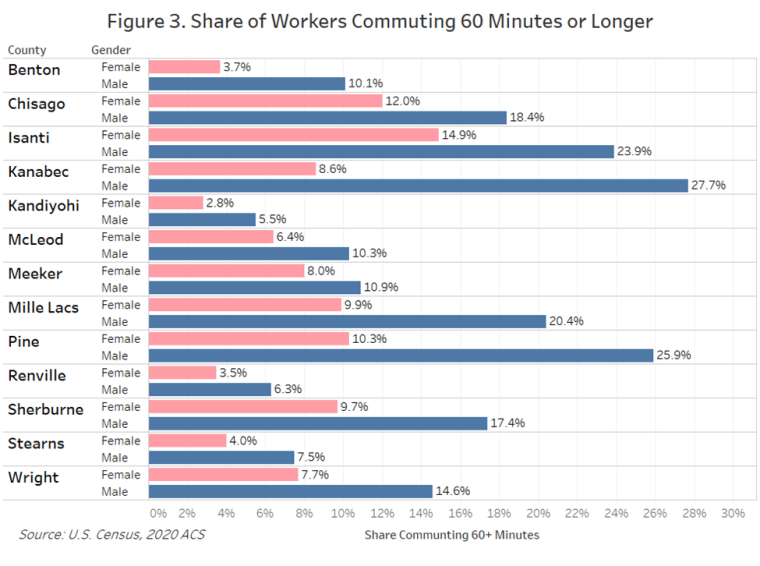

Long-distance commuters (60 minutes one-way or more) in Central Minnesota are much more likely to be men, accounting for 67% of workers who commute 60 minutes or more compared to just 33% of long-distance commuters who are women. This is another indicator of how professional and family responsibilities are allocated in households by gender. The average commute time for workers in Central Minnesota was 27 minutes with Isanti County topping the average length at 35 minutes and Kandiyohi County with the shortest at 17 minutes.

Figure 3 illustrates how common these long commutes are in certain counties, especially those that border the Twin Cities. In Kanabec County nearly 28% of male workers commute 60 minutes or more to work compared to “just” 8.6% of female workers. It’s a similar story in Pine County. Both have alluring highways that lead workers directly to Twin Cities employers. There are two main takeaways to these data:

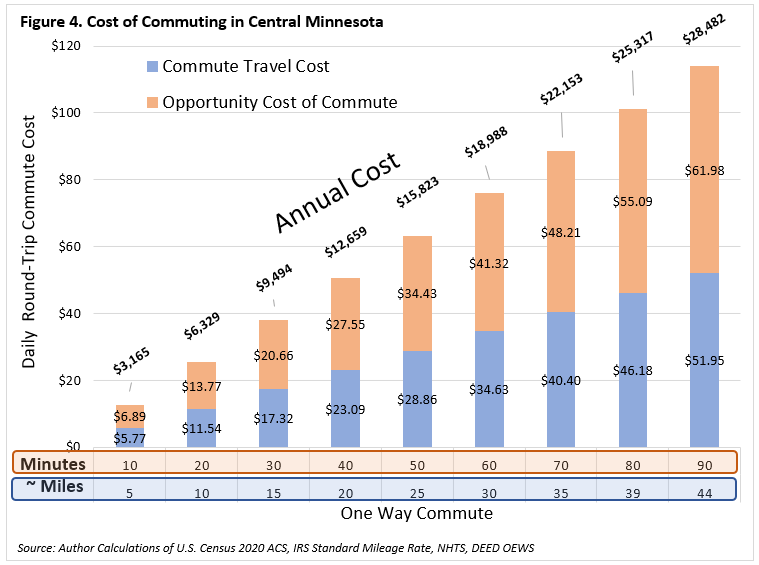

Not only is commuting long distances costly in terms of time, but it’s also just plain expensive. The IRS standard mileage rate in 2022 is 58.5 cents per mile, this includes gas, repairs/maintenance, insurance, depreciation, license fees, tires, car washes, and lease payments. This represents the travel cost of commuting. An additional cost that should be included is the time cost of commuting, known in economics as opportunity cost. The opportunity cost is how much could have been earned by working locally instead of leaving the region for employment. If a worker has an average commute but then decides to drive further in order to get a higher wage, should he or she accept the offer? Or would they be further ahead if they simply worked extra equal to the amount of additional time spent driving further? Adding these two costs provides a more complete understanding of the cost to commute.

The travel costs and opportunity costs are shown at various intervals in Figure 4. The commute time is translated to miles using the average commute speed for rural workers, it was 29.6 mph in 2017 according to the National Household Travel Survey. The opportunity cost uses the median hourly wage for all occupations in Central Minnesota ($20.66).

Most commuters probably complete a mental accounting exercise to grasp the costs associated with traveling, but it should be more sophisticated than just tallying gas receipts. It’s easy to see how overlooking the opportunity cost of commuting can be a sizable mistake.

The formula for the total cost of commuting is:

Cost of Commuting = ((commute miles *$0.585) + (commute time in minutes * (hourly wage /60))) * 2

Even a short commute time of just 10 minutes costs workers roughly $3,165 annually while driving for 60 minutes costs a staggering $28,482 every year. Just three years ago it seemed unlikely to have a commute shorter than 10 minutes, but by 2022 a job with no commute is not only possible, it’s common. This change in where people work has implications that span from the bank account to family dynamics and parental responsibilities.

Since each occupation has different wage ranges and the wage difference between Central Minnesota and the Twin Cities is also different, it’s impossible to come to broad conclusions on who should or should not commute out of Central Minnesota for work. However, analyzing the occupational wage differences between Central Minnesota and the Twin Cities and the potential extra time spent commuting provides an idea of what occupations are likely worth driving further for and which ones aren’t.

Figure 5 lists occupations by the net wage “payoff” for commuting 60 minutes into the Twin Cities from Central Minnesota. This calculation is simply the annual difference in median wage between Central Minnesota and the Twin Cities. The cost of commuting then needs to be subtracted from the wage difference. To show only occupations that have a net positive (median) wage gain from commuting into the Twin Cities set the slider bar to the annual cost of commuting from the formula above or from Figure 4.

Postsecondary Health Specialties Teaching jobs have the largest pay premium, with a median wage that’s almost $48,000 more in the Twin Cities than Central Minnesota. This occupation and others at the top of the chart are most likely to be worth driving long distances to the Twin Cities for. But most occupations have much lower pay premiums, making it less likely to come out ahead by driving long distances if similar employment is available closer to home.

Workers obviously benefit from understanding if driving extra distances for work is a sound financial decision, but employers also stand to benefit, especially with labor market boundaries becoming more blurred and easily crossed. As some workers are requested back to the office after two years without long commutes it seems now is an excellent time to capitalize on local opportunities.

Some commuting into the Twin Cities for work will always exist, yet increased opportunities for remote work should certainly decrease the numbers who continue doing so. The volatility of fuel prices also play a role. With current gasoline prices at record highs it should make workers think twice about the tradeoff of commuting. This shift will help some employers and hurt others depending on their ability to capitalize on this trend, but it should be a positive leap for rural workers everywhere, especially those who might be on the labor force sidelines caused by family dynamics and responsibilities.