by Molly Ingram

September 2024

In June we began a new Trends series on workforce considerations related to advancing Minnesota's Climate Action Framework goals. The first article defined common terms and presented green and clean employment estimates under definitions used by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and the U.S. Department of Energy. In order to understand the current research on clean economy jobs, and because there is no standard definition of the "green economy" or "green jobs", it is necessary to understand the definitions used in key federal reports and how most other reports either build off of those definitions or the underlying data sources.

The BLS's "Green Goods and Services" definition of green jobs and the U.S. Department of Energy's definition of clean energy jobs are both based on industry-level employment data. Many common employment, unemployment and wage statistics are constructed from industry-level employment data reported in the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW).

As an alternative (or complement) to the industry-based approach to measuring green jobs, some organizations and reports define green jobs by occupation. Occupations reflect what workers do while industries reflect what firms produce. Industry-level information is crucial to understanding how strong our economy is through statistics like GDP, and occupation-level information is crucial to understanding how strong our workforce is because it connects employment information to education, training and licensure information. Basically, occupations link labor-supply and demand information that governments, education institutions and other workforce development agencies depend on when preparing people for a changing labor market.

We know transitioning to a low-carbon economy will lead to both increases and decreases in specific jobs and will change the skills required as technologies change. Occupation data helps us evaluate what skills are in high demand, potential gaps in training opportunities, and the economic return on different skills. With this in mind, the following sections provide background information on how occupation data are collected and summarize how occupation information is currently being used to understand the workforce implications of climate change adaptation and mitigation.

Occupation-level employment data come from the Occupational Employment & Wage Statistics (OEWS) survey managed by the BLS and state workforce agencies (DEED's Labor Market Information office in Minnesota. The survey collects information from nearly 1.1 million establishments over a rolling three-year period and is designed to be representative of industries (3-digit or 4-digit NAICS level) as well as representative of states, metropolitan and non-metropolitan statistical areas.

The ability to disaggregate occupation-level employment data by industry and/or geographic region allows for a more accurate picture of employment changes. For example, if employment in a specific industry rises or falls, we do not know whether the industry is scaling up or down in response to demand shifts or if the industry is undergoing a transformation in production methods or something else. By looking at the changes in occupations within that industry, we can see how increases or decreases vary across occupation to get a sense of industry-wide impacts or occupation-specific trends. Disaggregated occupation-level employment data also helps differentiate education, training and licensure requirements (and corresponding wage differences) for the same occupation across different industries.

Occupations are classified according to the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) system overseen by several federal agencies including the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL). The DOL's Employment and Training Administration (ETA) sponsors the Occupational Information Network (O*NET), which provides detailed occupation information, including specific tasks, technological skills and other characteristics or requirements. Occupation classifications are reviewed and updated approximately every ten years in an attempt to capture how jobs are changing in response to economic and technological changes.

These revisions are especially relevant for occupations critical to climate adaptation and mitigation efforts, which are experiencing large shifts in technologies and processes. In acknowledgement of this, O*NET has supported two research programs on green occupations. The first began in 2009 and focused on greening occupations (defined in the following section). The second began in 2022 and focused on identifying occupations associated with green topics (also defined below).

O*NET took up the challenge to identify occupations most impacted by the green/clean economic transition in 2009. Researchers began by identifying "greening" occupations, i.e. jobs experiencing changes in work and/or worker requirements in response to changing economic activities and technologies associated with increased energy efficiency, reduction of pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, or other environmentally beneficial activities (Dierdorff et al. 2009). Occupations were grouped into three categories:

In 2022, O*NET broadened their green initiative focus from greening occupations to occupations related to green topics. A total of 72 green topics were identified after reviewing the previous O*NET greening occupation research and more current publications (Lewis, Morris, and Gregory 2022). The list of green topics includes agriculture, energy trading, health and safety, eco-tourism, atmospheric science, land use planning, and urban and regional planning, among others. In contrast, the earlier greening occupation research reviewed occupations related to 12 sectors of green economic activities including energy generation, energy efficiency, transportation, construction, agricultural and forestry, manufacturing, waste, etc. Although there is overlap between the green topics and green economy sectors, only 67% of occupations present in Minnesota's 2023 OEWS data that were flagged in 2009 were also included in the 2022 list of occupations.

A main reason for this discrepancy is the different objectives of the two O*NET research projects. As stated above, the objective of identifying greening occupations in 2009 was to determine the degree to which green economy activities differentially impact occupational requirements. The green economic activities considered were those "related to reducing the use of fossil fuels, decreasing pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, increasing the efficiency of energy usage, recycling materials, and developing and adopting renewable sources of energy"(Dierdorff et al. 2009, pg. 3). This work resulted in recommendations for additions to the O*NET-SOC taxonomy and updated occupation-specific task lists on O*NET (Dierdorff et al. 2011; O*NET 2010). The primary public output generated by the green topics research is a search tool that lists occupations and education programs to assist "individuals who want to incorporate green and environmentally friendly activities within their career exploration, job search, and preparation"(Lewis, Morris and Gregory 2022, pg. 3).

It is helpful to think of occupations associated with O*NET's green topics as occupations where the focus of work is changing or has the potential to change. For example, Chief Executive Officers, Epidemiologists and Community Health Workers are all listed as occupations related to the green topic of Environmental Health and Safety (and not considered greening occupations in 2009). While CEOs, Epidemiologists, and Community Health Workers may spend more time on joint environmental and economic considerations in their work now than 5, 10 or 15 years ago, those considerations are less likely to be a requirement of the occupation's work.

In contrast, greening occupations are those that have a direct role in environmental adaptation and mitigation efforts, such as Civil Engineers, Landscape Architects and Power Plant Operators. Not all occupation-specific tasks for these occupations are green, i.e. directly "related to reducing the use of fossil fuels, decreasing pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, increasing the efficiency of energy usage, recycling materials, and developing and adopting renewable sources of energy" (Dierdorff et al. 2009, pg. 3), but they all have at least one green task. The average share of green tasks per occupation is slightly less than 50%. Examples of occupations with only one or two green tasks include arbitrators who may oversee negotiations about natural resource uses, or machinists who ensure scrap materials are reused, recycled or disposed of appropriately. Examples of occupations where all tasks are green are Renewable Energy Engineers, Refuse & Recycling Material Collectors, Chief Sustainability Officers, and Weatherization Installers & Technicians (O*NET 2010).

Table 1 reports total employment, employment in greening occupations as defined by O*NET, and employment associated with green topics as defined by O*NET, for Minnesota in 2023 grouped by major occupation group. The six largest occupation groups, each with more than 50,000 people working in greening occupations, are Management, Transportation, Production, Office & Administrative, Construction & Extraction, and Installation, Maintenance & Repair occupations. For all of those occupation groups, except Office & Administrative, greening occupations make up more than 40% of all employment, ranging from 73% of employment in Construction & Extraction occupations to 45% in Transportation occupations. However, the occupation group with the largest share of greening employment is Architecture & Engineering at 85%.

Green topic-associated employment is generally larger than greening employment because more occupations are linked to a green topic than are considered a greening occupation, 312 occupations versus 204, due to the projects' different research focuses as discussed above. This difference in focus (occupations directly involved with emission, pollution, and waste reduction vs. occupations that may engage in green or environmentally friendly activities), as also discussed above, account for the few occupation groups where greening occupation employment is larger than green topics employment.

| Table 1 : Employment by Major Occupation Groups, Minnesota 2023 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Occupation Group | Total Employment | Greening Occ. Employment* | Green Topic Employment* |

| All | 2,827,310 | 666,810 | 789,780 |

| Management | 193,760 | 105,960 | 126,850 |

| Transportation and Material Moving | 227,780 | 101,960 | 65,080 |

| Production | 209,380 | 96,300 | 66,550 |

| Office and Admin Support | 345,830 | 82,980 | 37,820 |

| Construction and Extraction | 113,930 | 82,800 | 87,330 |

| Installation, Maintenance, and Repair | 98,670 | 57,380 | 7,980 |

| Architecture and Engineering | 53,100 | 45,400 | 48,240 |

| Computer and Mathematical | 99,250 | 36,360 | 62,390 |

| Business and Financial Operations | 201,940 | 22,330 | 54,880 |

| Sales and Related | 239,500 | 14,940 | 15,750 |

| Life, Physical, and Social Science | 29,070 | 12,060 | 17,220 |

| Arts, Design, Entertainment, Sports, and Media | 37,630 | 7,720 | 0 |

| Farming, Fishing, and Forestry | 4,060 | 590 | 4,020 |

| Legal | 18,730 | 30 | 18,730 |

| Community and Social Service | 54,820 | 0 | 26,590 |

| Education and Library | 158,830 | 0 | 14,830 |

| Healthcare Practitioners and Technical | 186,700 | 0 | 77,430 |

| Healthcare Support | 162,400 | 0 | 0 |

| Protective Services | 40,620 | 0 | 20,310 |

| Food Preparation and Serving Related | 216,970 | 0 | 0 |

| Building and Grounds Cleaning and Maintenance | 76,210 | 0 | 19,070 |

| Personal Care and Services | 58,120 | 0 | 18,710 |

| *Includes occupations with SOCs reported in OEWS which covers more than 90% of the O*NET-SOC occupations labeled green. | |||

| Source: Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics | |||

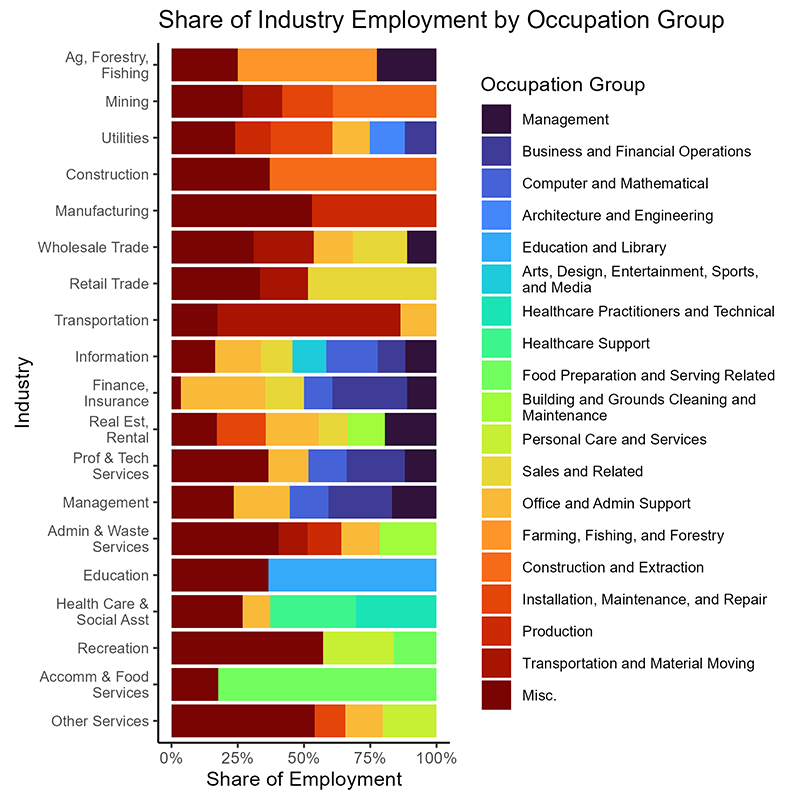

Industries encompass a wide variety of occupations. On average, Minnesota's 19 industry sectors have jobs in 20 out of 22 major occupation groups and 276 out of 820 detailed occupations. Even at the industry group level (4-digit NAICS), industries have jobs in 13 out of 22 major occupation groups and 86 out of 820 detailed occupations. Because of this diverse mix, it is often helpful to quantify industry workforce differences by measuring the share of each occupation's employment relative to industry employment. While each sector has workers in between 16 to 22 major occupation groups, the number of major occupation groups with more than 10% of a sector's workforce only ranges from 1 to 6 groups per sector.

Figure 1, below, indicates the share of employment for each occupation group with more than 10% of employment by sector, with all other groups' employment included under the miscellaneous group label. Some sectors are dominated by one key occupation group, such as Production occupations for the Manufacturing sector and Transportation & Material Moving occupations for the Transportation & Warehousing sector. Other sectors' workforces are more evenly distributed across occupation groups, such as the Management of Companies, Information, and Administrative Support & Waste Management sectors. Studies occasionally use these differences in industry-occupation prevalence to categorize jobs, such as this clean energy jobs report from the Brookings Institute, which defines clean energy jobs as those in occupations that are over-represented in specific clean energy industries, e.g. renewable energy generation, energy efficiency improvements and waste management, relative to national employment (Muro et al. 2019).

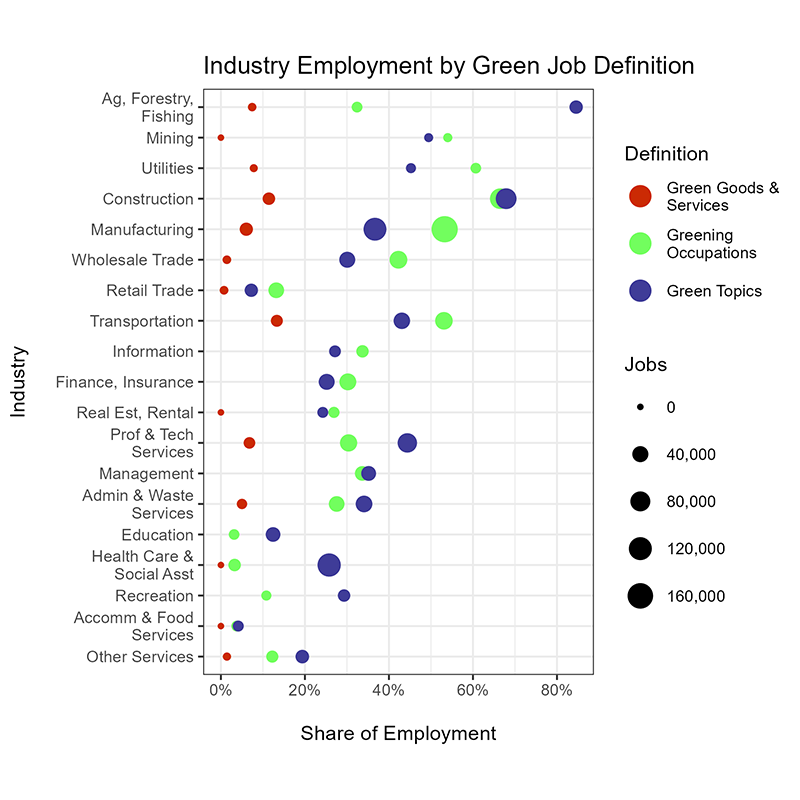

Because occupation employment can be linked to industry, we can also compare the BLS's industry-based green goods and services (GGS) employment estimates to O*NET's occupation-based greening occupations and green topics employment. Figure 2, below, reports the share of green employment by industry based on the GGS, greening occupations, and green topics definitions of green jobs using statewide 2023 employment data. The color of a dot indicates which definition the industry employment share corresponds to, and the size of a dot represents the number of jobs in the industry under the green job definition. The occupational approaches cover nine or 10 times more workers than the BLS's industry-based GGS definition. Some of this difference is because the GGS measure is a very conservative estimate (see the first article in this series for an explanation why). However, the larger variation in green employment under the industry- and occupation-based definitions is mainly a result of the GGS employment measure methodology. The BLS estimates GGS employment based on the share of a firm's revenue generated from selling green goods and services (Ingram 2024; Bureau of Labor Statistics 2013). By focusing on the final product, the GGS measure cannot capture changes in the production process, such as activities that increase energy efficiency or reduce pollution and waste for the firm overall, regardless of the final product. Despite the differences in the size of employment under each measure, the Manufacturing, Construction, Transportation, Professional & Technical Services, and Administrative Support & Waste Management sectors are all among the top 5 or 10 largest green employment sectors by any of the three definitions.

The occupational approach to measuring green employment has a few advantages over the industry-based approaches presented in the first article in this series. First, it is easier for states and smaller geographic regions to implement because it does not require a survey to split out green/clean production from not, as required for the BLS's GGS methodology and the U.S. Dept. of Energy's Energy Employment Report methodology. Second, it captures changes in production processes that are overlooked by focusing on final production, such as process changes to increase energy efficiency. Additionally, occupation data may be more useful to governments' workforce planning efforts because it connects jobs to education and training programs.

However, there are some drawbacks to an occupational approach. One is the ambiguity over what occupations should be considered green as illustrated by the differences in O*NET's greening occupations and green topic occupations. A second drawback is its aspirational nature. Unlike the industry-based definitions, there is no confirmation that individuals employed in flagged occupations are actually engaging in green, environmentally beneficial activities. Companies may or may not require machinists to recycle scrap materials or reduce waste. Best practices for building and landscape architects may include designing projects to minimize environmental costs and exposure to extreme weather risks, but we cannot confirm this is followed without collecting more detailed data.

Regardless of the challenges, adding the occupational approach to our toolkit helps us develop a more inclusive understanding of workforce needs and the role of employment as global, national, state and local economies transition to a lower-carbon future. Viewing employment through the lens of occupations also reinforces the different ways climate adaptation, mitigation and resiliency efforts can impact work, whether by changing the technology and processes used or by changing the focus of, or information needed to perform, a job.

As is always the case, governments, public and private businesses, educational institutions and individuals will need to decide what employment information is necessary to meet their planning needs and whether or how to collect it. DEED's Labor Market Information office continues to study existing climate- and economic-related labor force data in support of Minnesota's Climate Action Framework update, which will be released next year along with detailed workforce and economic development reports from DEED. If you have questions about the impact of climate adaption and mitigation on to Minnesota's economy and workforce, please send them to molly.ingram@state.mn.us.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2013. "Green Goods and Services Employment." March 19, 2013.

Dierdorff, Erich C., Jennifer J. Norton, Donald W. Drewes, Christina M. Kroustalis, David Rivkin, and Phil Lewis. 2009. "Greening of the World of Work: Implications for O*NET-SOC and New and Emerging Occupations." February 2009.

Dierdorff, Erich C., Jennifer J. Norton, Christina M. Gregory, David Rivkin, and Phil Lewis. 2011. "Greening of the World of Work: Revisiting Occupational Consequences." December 2011.

Ingram, Molly. 2024. "Green and Clean Employment in Minnesota: A Starting Point." Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development. June 2024.

Lewis, Phil, Jeremiah Morris, and Christina Gregory. 2022. "Green Topics: Identifying Linkages to Occupations and Education Programs Using a Linguistic Approach." June 2022.

Muro, M., A. Tomer, R. Shivaram, and J. Kane. 2019. "Advancing Inclusion Through Clean Energy Jobs." Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings.

O*NET. 2010. "O*NET Green Task Development Project." November 2010.