by Luke Greiner

June 2023

Central Minnesota, like all regions of Minnesota and most parts of the country, is facing a tight labor market that is likely constraining job growth across multiple industry sectors, impacting some industries more than others. In many cases, employers want to hire more workers and create more jobs, but can't find the workers they need, limiting job growth.

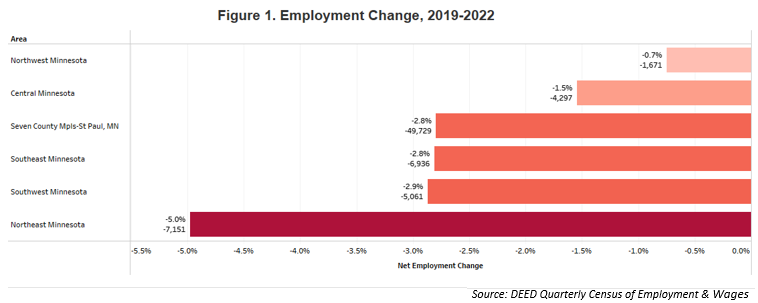

Roughly three years after the brief Pandemic Recession in 2020, every region in Minnesota still has fewer jobs than it had in 2019, at least when looking at annual averages from the Quarterly Census of Employment & Wages program. Central Minnesota has shown remarkable resilience, achieving the second smallest overall decline of from 2019 to 2022 (-1.5%).

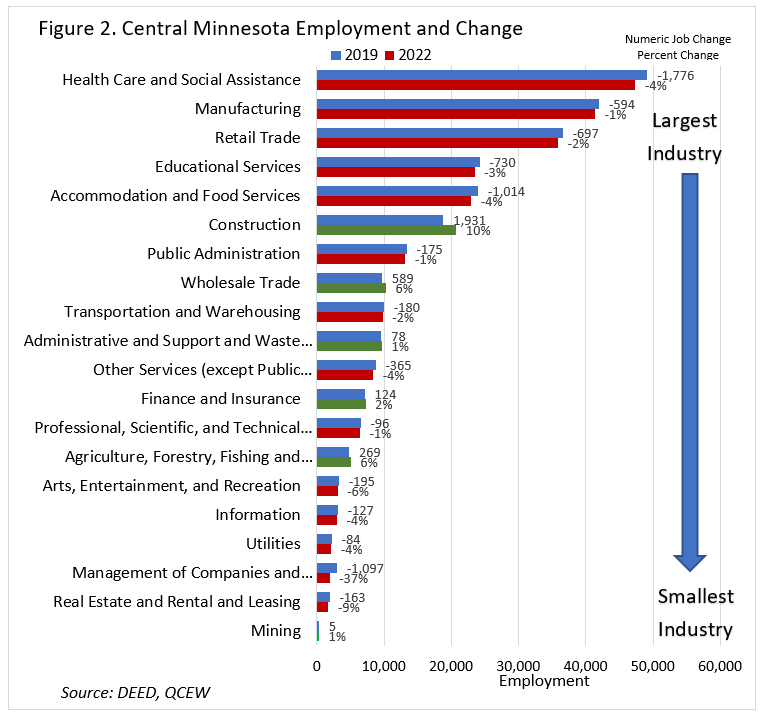

In Central Minnesota, the negative job change from 2019 to 2022 comes out to 4,297 fewer jobs. There were some industry sectors that managed to thrive during the volatile past few years, finding the workers they needed and adding jobs. These bright spots included Construction, which grew by 10%, and Wholesale Trade, which saw 6% growth. Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing & Hunting, Administrative Support & Waste Management Services, Finance & Insurance, and Mining also added jobs over the period.

A tight and challenging labor market has kept employment growth stubbornly slow across the broader economy. The five largest sectors remain below their pre-pandemic employment levels, with Accommodation & Food Services off 4% with 1,014 fewer jobs in 2022 than 2019. Even Health Care & Social Assistance and Manufacturing haven't fully recovered despite strong demand for their services and goods (see Figure 2), further evidence of labor market tightness constraining job growth.

Looking at industries in more detail shows the nuances of job gains and losses in our economy from 2019-2022.

Notable job gains came from:

The largest job losses occurred in:

Most of the job losses are resulting from a lack of workers able to fill job openings, with the exception of job losses in Electrical Equipment, Appliance, & Component Manufacturing, which was primarily due to Electrolux moving operations to a different state.

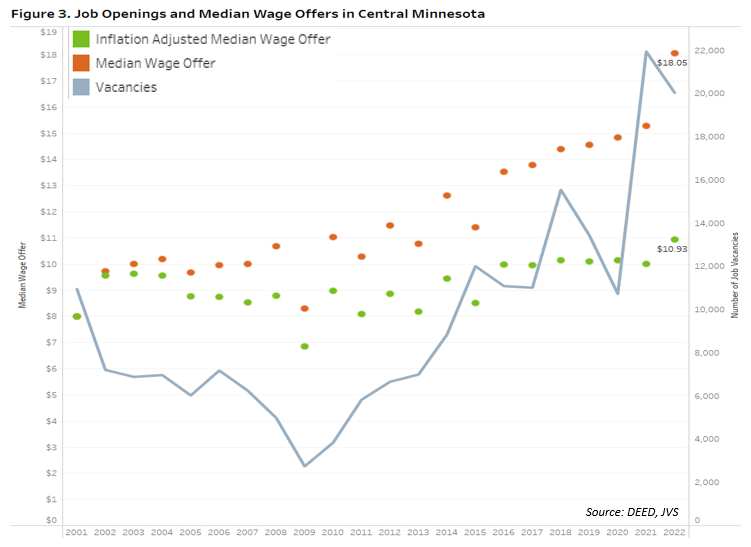

As the Pandemic Recession was unlike any other, so has been the recovery. Central Minnesota had more than ten times the number of job openings compared to 2009, the year the Great Recession officially ended. Record numbers of job openings across most sectors indicate just how tight the labor market is and what the real recovery issue is: a lack of workers. Despite favorable labor market conditions for workers to wield their power, real wage growth for openings has hardly budged since 2016. Vacancies in 2022 finally saw a gain in wage offers after adjusting for inflation, but real gains weren't evenly distributed across occupational categories.

Food Prep & Serving Related occupations had the largest number of openings but also saw the inflation- adjusted median wage offer decline slightly, while the next six most common occupational categories saw wage offers increase in real terms: Sales & Related, Transportation & Material Moving, Healthcare Practitioners & Technical, Production, Construction, and Healthcare Support occupations. While stagnant wage growth isn't exactly celebrated, it may help prevent already high inflation from increasing further due to wage growth (see Figure 3).

Job Vacancy Survey data show that employers have been responding to the dwindling pool of job seekers by lowering educational requirements that can filter out interested candidates who don't possess the "required" or "preferred" degrees. While certain occupations – particularly licensed healthcare related occupations – are unable to adapt to changing labor market dynamics, the vast majority of occupations have much more flexible requirements now than coming out of the Great Recession 10 years ago.

Businesses are revisiting educational requirements to determine how necessary higher education is to perform the vital functions of their jobs. In some cases, occupations that were filled by college graduates are now being filled by workers with relevant skills and experience. This provides a benefit to companies as they can broaden their search for more applicants to find the best fit, and it has the added benefit of providing opportunities to workers who lack a higher education credential.

The correlation between educational demand by employers and the labor market indicates that the future need for workers with higher education will be somewhat limited by the availability of labor. If labor force constraints continue, educational requirements to get a job will likely continue to drop (see Figure 4).

Despite the remote work shift that rapidly occurred in 2020, which is one of the most dramatic changes in our economy in recent history, educational needs remained mostly unaffected. Most occupations that have high rates of work from home options already required computer and technology skills, which are both a necessity to be successful working from home. If the future of work includes increasing numbers of workers working from home, they will need capable technology and computer skills, not necessarily a college degree.

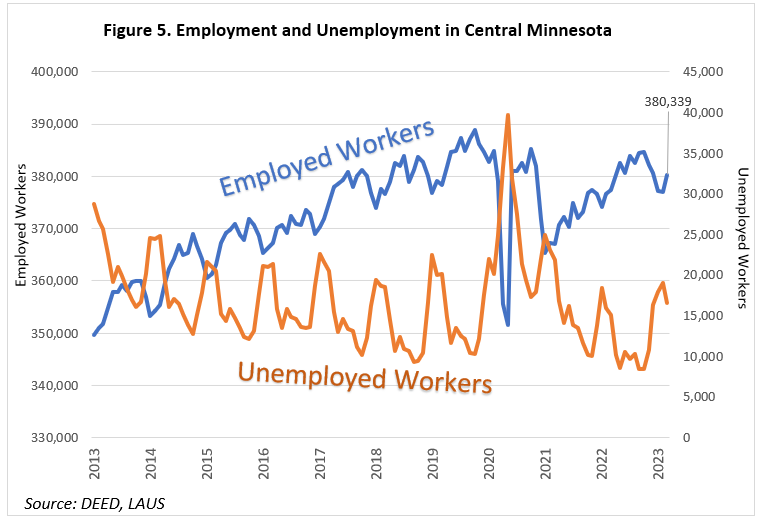

The region's record low unemployment rates reflect that Central Minnesota has historically low numbers of unemployed workers who are available and looking for work. After spiking in the beginning of the pandemic, the number of unemployed workers fell dramatically in the summer of 2021 to numbers similar to pre-pandemic years and have stayed low since then.

Meanwhile the number of workers who were employed continued to slowly climb after bottoming out in January of 2021. Most recently in March of 2023, there were an estimated 380,339 workers employed, down roughly 4,600 compared to February of 2020. Fewer workers working and less workers looking for work means a smaller labor force.

The outcome of this ripples through the entire economy: raw materials might take longer to receive, finished products might take longer to produce, or fewer restaurants might be open, and the remaining establishments might have limited hours of operation due to lack of staff. The past few years saw Central Minnesota's economy have less employment and fewer workers compared to 2019.

As employers struggle to claw back employment lost in 2020 and the Federal Reserve uses their levers of monetary policy to bring down inflation, the scarcity of workers remains a challenge and somewhat at odds for both the goals of employers and the Fed. On one hand, cooling down the economy via raising interest rates usually leads to more slack in the labor market, but on the other hand the tight labor market emboldens workers to negotiate higher wages in order to keep up with inflation, thus leading to higher costs for goods.

In essence, the tight labor market works against both the ability of employers to easily fill openings, and the effectiveness of monetary policy. Aside from maintaining stable prices the other task assigned to the Federal Reserve is to maintain "full employment". The silver lining is that workers across various demographic groups are benefiting from recent wage growth in real terms and historically low rates of unemployment.

Central Minnesota had an average of just 11,887 unemployed workers throughout 2022, similar to the number the region had back in 2000. The nearly 12,000 unemployed workers include workers who are unemployed for very short periods due to changing jobs or moving, meaning all unemployed workers aren't necessarily all available to fill openings. Over the same period, the region's economy added over 37,000 jobs, a 16% increase. On top of that job growth, there were also workers transitioning between occupations or out of the labor force, increasing the number of openings employers need to fill just to maintain staffing levels. With the same number of unemployed workers, the area had more than two decades ago, when the region's total number of jobs was significantly smaller, the challenge for employers looking to hire is real (see Figure 5).