by Luke Greiner

November 2019

If you think every worker who wants a job has a job in today's strong economy, think again. While it might be a true statement relative to previous economic conditions, the statement easily glosses over the numerous workers who have recent work experience yet find themselves unemployed. Employment churn within our economy leaves many workers jobless, even during a time of historic economic growth and record low unemployment rates. Any large layoff can cause upheaval in the lives of workers.

Will these workers who are laid off through no fault of their own – a requirement for collecting unemployment insurance benefits – find a replacement employment opportunity with ease? Again, it's relative to the labor market, but finding similar employment in a timely manner within a reasonable driving distance can be difficult even in the best of economic times. In Central Minnesota almost as many job vacancies exist as unemployed workers available to fill them. The current jobseeker-per-vacancy ratio in the region is 1-to-1 and even dropped below one during 2018 as the number of vacancies increased.

Thanks to data from Minnesota's Unemployment Insurance (UI) program, we know more about who is laid off and currently seeking work. Minnesota's UI statistics provide demographic characteristics of people who file initial claims for unemployment insurance, including details on occupation, industry, education level, race, sex, and region of claimants.

This analysis will look at the workers in Central Minnesota who qualify for UI benefits. It's important to note that there are other unemployed workers who are not included in this dataset. For information see the Who's Included sidebar below.

To qualify for unemployment insurance benefits, applicants must have earned sufficient wage credits and must be unemployed through no fault of their own, available to work, and actively seeking suitable employment. Not every unemployed worker applies for unemployment insurance benefits. Therefore, the UI statistics capture only one segment of all unemployed.

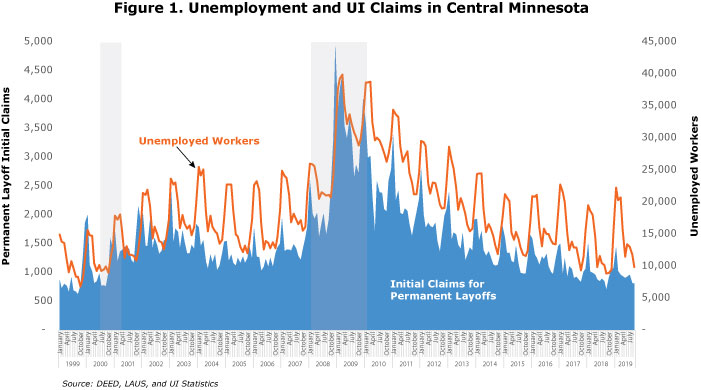

Mirroring our unemployment rates, the UI claims for initial permanent layoffs are relatively low, indicating that we do not appear to be on the cusp of a major change in the business cycle. Although this is just a single measure, it's easy to see how well UI claims data plotted the front edge of the past two recessions. Since the beginning of the year through the most recent monthly data in September, five months had fewer applicants than the previous year while four saw a small uptick. This would indicate that the regional economy is still moving ahead with typical expansionary gusto (see Figure 1).

The only time that there were fewer initial UI claims filed was in the year 2000, but keep in mind that the region has 42,375 more jobs in 2018 than it had at the turn of the century, so the share of UI claims compared to employment is actually smaller now.

To add some perspective, in the region the average monthly initial UI claims for permanent layoffs in the first nine months of 2019 was just over 2,000. During the first nine months of 2009, Central Minnesota averaged more than 5,300 initial UI claims for permanent layoffs. For jobseekers the high rate of layoffs meant large numbers of experienced competition applying for a decreasing number of job openings, and for businesses it meant a surplus of labor that they were able to pick over for the very top candidates to fill openings.

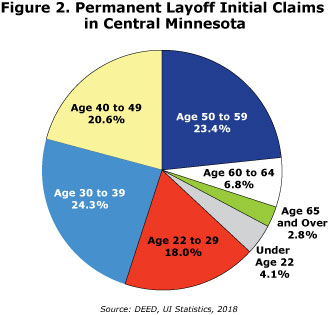

As you can see in Figure 2, the largest numbers of permanently laid off workers filing for UI benefits are 30-39 year olds, accounting for 24 percent of claims. Following closely are workers 50-59 years old at 23 percent. Workers 65 years and older comprise just 2.8 percent of claims, even though they make up 4.4 percent of the regional labor force. While this doesn't refute age discrimination claims, the oldest workers are less likely to be permanently laid off through no fault of their own and file for unemployment insurance. Instead it's possible that many retire instead of searching for another job.

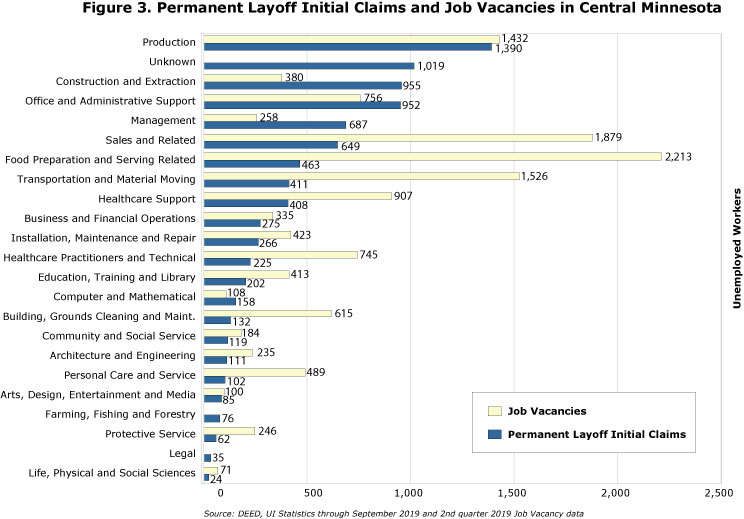

A severe limitation with UI statistics is the dependence on self-reporting by applicants to determine more nuanced options such as industry and occupation. This is clearly seen in Figure 3 where the second largest number of permanent layoff initial claims are filed in the " Unknown" occupation category. This clouds things a little. It's likely, however, that not all occupations fall victim to such ambiguous reporting. For instance, workers in Construction occupations (carpenters, drywall installers, electricians, etc.), probably have little difficulty knowing that their job is contained within the Construction and Extraction occupational group.

Initial UI applicants are most likely to be laid off from production occupations at Manufacturing establishments. This makes sense intuitively since Manufacturing is the second largest industry in the region. Holding all other variables constant, we would expect Manufacturing to have the second largest number of claims. The claims are also consistent with the number of initial claims for workers in production occupations that occur almost exclusively in Manufacturing.

Combining job vacancy data with permanent initial layoff claims displays a measure of the opportunity that laid off workers likely find in the labor market. Nearly every occupation has more vacancies than workers from it who are filing for unemployment insurance, meaning there is room to absorb at least a share of laid off workers. Of course, these broad categories gloss over how important specific skills are in the labor market. While not every unemployed worker holds the right set of skills to fill every opening, the numbers are in their favor. Larger numbers of job vacancies provide for more variety in the opportunities and skills employers are looking for.

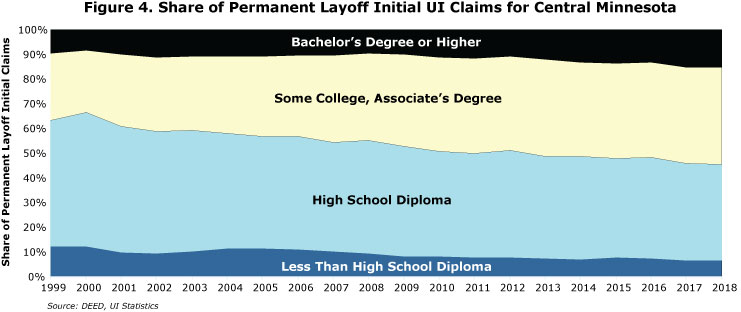

Sometimes data refuse to obey commonly accepted beliefs or evidence supported by other datasets. The educational attainment of workers filing for unemployment insurance seems to go against the adage that workers at the lowest levels of educational attainment are increasingly susceptible to negative externalities within the economy. But the share of initial UI claims for permanent layoffs filed by workers without college has been steadily falling since 2004. One reason for the decline is the increasing number of workers attaining some levels of higher education, leaving fewer with lower education in the labor market able to be laid off. In 2009, 63 percent of workers in Central Minnesota had some amount of post-secondary education; by 2017 that proportion grew to 69 percent. The change, however, is not large enough to explain the long term trend in UI claims.

It's true that workers with a high school diploma or less do not have a degree to fall back on when seeking employment to replace the job they lost, yet workers with lower educational attainment who filed for unemployment insurance from a permanent layoff were less likely to be laid off during the recession than those with higher levels of education. The same is also true for continuing claims, not just initial filings. Layoffs during and since the Great Recession have not disproportionately impacted workers without a college degree. The data also suggest that having a college degree does not make a person immune to layoffs, as might have been previously thought.

As our economy continues to chug along and all systems are go, don't forget that churn within our economy is happening right under your nose. Understanding who our recently laid off workers are and what skills they have might be an excellent recruitment strategy. Employers looking to connect with workers who have been laid off can contact their local CareerForce location for help.