Historic redevelopment opportunities of this scale are few and far between, but funding is more competitive

1/12/2018 5:00:00 PM

Five years ago, the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development was on the ground floor of redeveloping the Pillsbury A-Mill Lofts in Minneapolis, once called the City of Flour and Sawdust. In 2012, DEED awarded the City of Minneapolis nearly $700,000 for cleanup and redevelopment, through two programs, the Contamination Cleanup and Investigation Grant Program and Redevelopment Grant Program.

Today the 251-unit housing development is completely occupied, with a waiting list for artist-tenants since opening in 2015. The Mill City Museum, built in the limestone Washburn A-Mill ruins, welcomes visitors with an appreciation for Minneapolis’ flour industry past. The Pillsbury A-Mill is a National Historic Landmark (one of 26 in Minnesota).

Converting a century-old flour mill that sat vacant through more than 10 Minnesota winters was extremely challenging, said Owen Metz, vice president and project partner.

“The A-Mill was the most difficult of the buildings to renovate and preserve for the next 100-plus years,” he said. “The building nearly collapsed in the early 1900s and was retrofitted with steel structure to stop the front façade from caving in and the building collapsing. As a result, the floors were not level and the columns were out of plumb. Significant mitigation was done to the floors to get them level before pouring concrete floor for fire protection and sound mitigation.

“Further, a vertical truss system was added at the exterior wall to reinforce that bowing front façade. Finally, an enhanced water sprinkler system was installed to specifically wet the unprotected steel columns in the event of a fire to protect them from failing.”

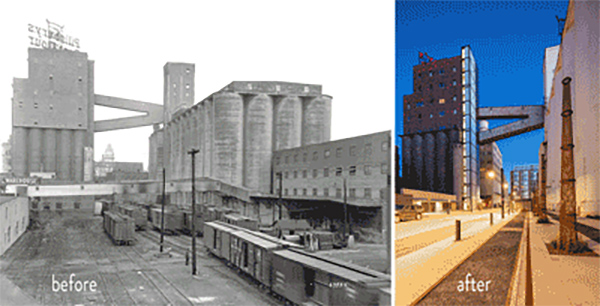

Some historic remnants of the building remain, both on the outside and inside of the building. The grain silos in the rear rail corridor behind the building are in place. Flour filters and other flour pieces have been repurposed to create vertical landscaping pieces, adding visual interest. An old railroad transfer table was preserved to showcase how the rail cars moved in the space.

“One of the more impressive interior features preserved were some of the Humphrey Manlifts that used to move people vertically throughout the tall buildings,” Metz said.

The Mill City Museum hosts walking tours in the building and around the site. Residents open up their homes and use their units and amenity space and studios to bring in outside parties. The 1st floor of the A-Mill has hosted numerous resident, public, and stakeholder events. “The water power infrastructure that was in-place was retrofitted with the approval of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to create a 600 kW hydroelectric microturbine in the basement, utilizing the power of the Mississippi River to provide most of the on-site electricity,” Metz said.

The redevelopment would never have occurred without the public-private partnership of the various financing partners — from tax-exempt bonds to affordable housing tax-credits to historic tax credits to DEED, Metropolitan Council and Hennepin County grants. “While there aren’t many historic redevelopment opportunities of this scale and complexity left in Minneapolis, much less the state, many factors of the financing model would be replicable,” Metz said. “However, getting access to these funding options are becoming harder and more competitive.”

“This project took a very knowledgeable, very professional, very experienced team to pull off.”

DEED’s Contamination Cleanup and Investigation Grant Program has awarded 507 grants worth more than $176 million since the program’s inception in 1995. Thanks to the funding, 3,547 acres of contaminated property have been reclaimed for development projects, resulting in 22,766 new jobs and 24,724 retained jobs. The program has attracted $6.6 billion in private investments and generated nearly $114 million in new tax revenue.

DEED cleanup grants – awarded twice a year – account for about 75 percent of funding used for reclaiming polluted sites and brownfields statewide. The remaining 25 percent comes from the Metropolitan Council, cities, counties, other local units of government, private landowners and developers.

The Redevelopment Grant Program helps communities with the costs of redeveloping blighted industrial, residential or commercial sites for planned projects. Grants pay up to half the redevelopment costs for a qualifying site, with a 50 percent local match required.

The program has awarded more than $66 million for 177 projects since it was created 19 years ago. Nearly 1,300 acres of blighted property have been returned to productive use in Minnesota with the help of program funding.

Twin Cities